The rise, demise and redemption of Live

From post-grunge kings to a busted flush, Live are on the rise once more

"I'll admit, after the first four Live albums, I kind of stopped listening," says Chris Shinn, a 40-year-old singer/songwriter who grew up a big fan of Pennsylvania post-grunge giants Live. Nothing particularly outrageous about that statement on the face of it. Except Chris Shinn is the new lead singer of... Live. "Well, to be honest," replies the band's guitarist and founder member Chad Taylor, "We stopped listening too."

That admission forms part of a sobering tale for any aspiring rock band, of how you can succeed beyond your wildest dreams but then become creatively trapped and disillusioned by that success and see lifelong friendships disintegrate along with it.

Thankfully for Live, the story now looks set to be one of despair followed by redemption, as the 2009 split with singer and chief songwriter Ed Kowalczyk — which they expected to spell the end of the band — now just appears to be the end of the beginning. Former Unified Theory frontman Chris Shinn joined the reformed Live in 2011 and made new album The Turn with them – 11 songs full of the kind of powerful, hook-laden stadium rock noir that hark back to the glory days of the early 1990s, when albums like Throwing Copper and Secret Samadhi clocked up over 10 million album sales.

Sipping bottled beers in a West London hotel bar, Live certainly seem to be in a way happier place than they were five years ago, when a planned two-year hiatus soon turned out to be a deeper rift, with Taylor pointing to questionable lead-singer behaviour: demands for a $100,000 ‘lead singer bonus’ to play a European festival, and changing the band’s publishing deal to make him sole signatory.

After making an album as the 70s-rock-oriented Gracious Few with Candlebox’s Kevin Martin, the pair decided to make reports of Live’s death premature, and when they considered potential singers for ‘Live 2.0’, there was no great debate as to who they should hand the mike to.

“We knew we weren’t going to be a ‘power trio’,” explains bassist Pat Dahlheimer. “And we weren’t going to play our own version of Jazz Odyssey.”

“There was no audition process,” explains Taylor. “We just all agreed we wanted to work with Chris.” To put that into context, Shinn was a long-time friend of the band who had guested on stage with them at several shows in the past. And he was pretty well acquainted with their back catalogue.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I knew how to play their songs better than they did,” he grins.

“We had never played a Live song without Ed, so we were pretty apprehensive,” admits Taylor. “And when we got together to rehearse, we hadn’t played those songs in years. But it clicked immediately. The roof didn’t fall in, and we all thought ‘this opportunity is pretty magical.’”

Playing with Chris also reminded the band of a time when, well, they really were a band.

“Yeah, on the past three records, we were basically just Ed’s backing musicians, trying to hang on in there. Chris came back and said, ‘look, this is what I remember and love about Live.’ And it really felt like something special again.”

“It felt like the badass version of Live,” says Shinn. “I mean, I remember the first time I heard Lakini’s Juice, and shivers went down my spine. That’s what I want to get back to.”

Part of the same process involved Taylor, Dahlheimer and drummer Chad Gracey going back to their roots.

“We knew we had to hit a certain mark,” says Taylor. “but what is that mark we set? So for the first time, we listened to the first four albums back to back.”

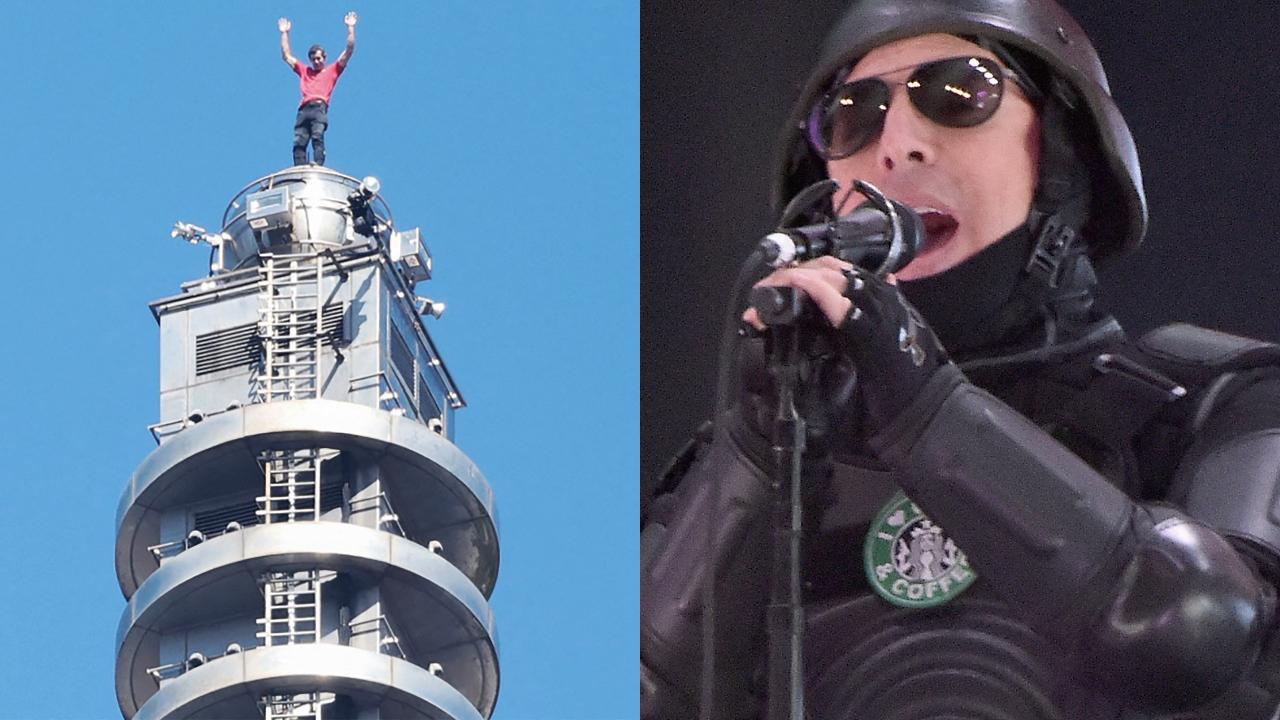

Live with original singer Ed Kowalczyk (second from right)

And that seems like a good cue for us to delve into the long, 30-year story of how they reached this point. Live were 13 and 14-year-olds when they first started playing together at middle school. After classmate Ed Kowalczyk saw them playing a school talent show, he asked to join the band, and before they were out of their teens, they earned the patronage of CBGBs founder Hilly Krystal, who helped them enlist the services of Blondie and Ramones manager Gary Kurfirst, and a deal with his Radioactive label followed.

This being the turn of the 1990s, of course, the grunge scene was just about to go seriously overground. Not that the young Pennsylvanians really felt part of it.

“We were these squeaky clean kids from the wrong coast – the non-grungy one!” says Dahlheimer, “We’d listen to the bands and think ‘that’s cool’, but they were contemporaries not comrades.”

“They were also older,” adds Taylor. “We still weren’t 21, so we’d have to ask them to sneak beer into gigs for us ‘cos we weren’t old enough!

“I do remember a real moment in time on one occasion though. We were staying at the Phoenix motel, in San Francisco, and our first single, Operation Spirit (from the Four Songs EP), was due to debut on MTV and we all gathered in a room to watch it. We had the door propped open and saw the guys from Nirvana walk by. We told them our video was about to debut and persuaded them to get some beers for us. Then around midnight we wandered to the lobby and sat shoulder to shoulder, watching Operation Spirit and Smells Like Teen Spirit play on MTV, back to back. We’re all shouting ‘we’re gonna be fuckin’ huge!’ Seven dumb-ass kids.

We didn’t know just how big Nirvana would go and how quickly Kurt would pass away, and how Dave Grohl would turn into a rock star in his own right. But I remember how exciting it felt back then.”

It wasn’t all fun and games, mind. Kurfirst tapped into his punk connections to get Live a support tour with the Ramones in those early days, and naturally, punk rock crowds weren’t always hugely receptive to teenage support bands.

“We’d play these venues with chicken wire across the stage, just like on The Blues Brothers, to stop people throwing bottles of beer at us,” remembers Dahlheimer.

After the release of their 1991 debut album Mental Jewelry, they toured with John Lydon’s PiL, and the punk legend offered some wise words. “He was really supportive, and would take our album out before we played and recommend it to people. Then one time we played in Manchester, the home of The Smiths, and we’re really excited, but we get bottles of piss thrown at us, and we come off stage saying ‘What the fuck?’ And he said ‘Oh it just means they love you!’

Still, if they weren’t well-known in the UK back then, they found that Johnny Rotten was by no means familiar to everyone back in the States.

“We played a show in Philadelphia, and we invited an old school friend of ours who only ever listened to rap music. We were hanging out with Lydon after the show, and our friend says to him, ‘So, what do you do?’ And he says, ‘erm, well, I’m in a band.’ ‘What sort of band?’ ‘A rock band.’

He still doesn’t get it, so Lydon says, ‘Have you ever heard of the Sex Pistols?’ And we were just cringing with embarrassment. But then Lydon just sits there, like a school teacher, and explains his whole career. He says, ‘OK, so we were part of what was known as the punk rock movement…’” It was just surreal.”

Within a couple of years, though, Live would follow up Mental Jewelry with 1994’s Throwing Copper, and with help from muscular singles such as I Alone and Lightning Crashes, they found themselves selling over eight million copies of the album in the US alone. Before they knew it, they were playing stadiums and experiencing the kind of pressures that 22-year-olds generally find a little tough to deal with.

“It was was such a heartfelt record, and so revealing,” admits Taylor, “partly because we thought we’d maybe sell, like, 200,000 copies if we were lucky and have time to grow up as a band. Instead it’s millions and we were like, “Oh hang on, I didn’t mean to stand naked in front of the class, but here I am. What do I do now?

Even the wise old heads from CBGBs didn’t really know what to tell them.

“We went to people like the Ramones and Talking Heads, and said, ‘what do we do?’ They were like, ‘we don’t know, your band is bigger than ours already!’ And I didn’t have Bono’s cellphone number to ask how to be in a big band.”

Naturally, most of the scrutiny was on the singer, and Ed Kowalczyk reacted by withdrawing, not just from the world at large, but increasingly his bandmates too.

“In defence of Ed, there’s no school to help you handle fame and all that comes with it, and his tool was isolation, as it was for us all. We isolated as a band, got bodyguards, and eventually we isolated from each other. We’d go months without talking.”

At first, the effect of success on four working-class kids was head-spinning (“I looked at my bank account one day, saw all these zeroes and said, ‘There’s got to be some mistake here.’”) and after the excesses that followed, Taylor concludes, “all I can say is I’m glad that nobody died, because they very easily could have.”

Naturally, the darker textures of Live’s next album, 1997’s Secret Samadhi, reflect ed a desire to shrink away from the spotlight.

“We ran to the hills,” laughs Taylor. “The sleeve was black, the first single was called Lakini’s Juice – and I challenge anyone to tell me what a lakini is to this day! – and we were basically trying to do anything but make Throwing Copper 2. Then The Distance To Here was a bit of a correction to that shift, but after that I think things were never quite the same again.”

One major reason for that shift in the band’s feelings about the band they’d been in since childhood was that after The Distance To Here, Kowalczyk, whose mystically-inclined, sometimes impenetrable lyrics had always been a trademark of the band, demanded he take charge of all songwriting duties.

At the same time, after two albums that sold substantially but couldn’t match the supernova success of Throwing Copper, the pressure was on to repeat the same success.

“The bar is raised, commercially speaking, people working for you expect to get their commission, and you find yourself chasing sales. And worse than that, I believe we went from being a trend setter – because we didn’t know what the trend was – to chasing the trends.”

Hence moves like enlisting rapper Tricky and the likes of Adam Duritz to guest on V, released in 2001, an album that was initially intended as a collection of studio sessions to give away to fans, but which the record label (by now swallowed up by MCA/Universal) insisted be released as an official album. Although the album provided highlights such as the breathtaking ballad Overcome (which became something of an anthem for the trauma of 9⁄11, having been released shortly afterwards, but which the label refused to issue as a charity single), the band found themselves being told to restyle themselves in the mould of then-hip acts like No Doubt, and when jobbing songwriters such as Glen Ballard were brought in, the band were further marginalised, told what notes to play, and so forth. Taylor has gone into more detail about that frustrating time on his blog.

“And all the time, people were like ‘well guys, you need to write another I Alone,” recalls Taylor. “We weren’t happy, but Live was all we knew, so when Ed says ‘I want all the songs and have sole credit from now on’, it took us 10 years to say ‘this is fucked up – fuck this, these songs are shit!’”

Two more albums, Birds of Pray (2003) and Songs From Black Mountain (2006) followed, but the rest of the band’s hearts were increasingly not really in it.

“It got to the point where I asked to have my name taken off the last record,” says Taylor. “It was basically Ed’s solo record, but management looked at it and thought, ‘well, if Mick Jagger can’t make a successful solo record outside the band, what chance does Ed have?’ So they wanted to put the Live name on it.”

“I think the fans, for a long time, kept Live going. They needed more music and we needed them, and we carried on until it was like ‘I don’t even know why we’re doing this.’ Not only were we ripping off the fans, we were ripping off ourselves, and betraying the dream we’d had since we were 10 years old. I dreamt back then of being a famous fucking rock star. And then all of a sudden you have that and you realise you’ve lost the credibility, the brotherhood, the appreciation of it. You’re living a lie.”

Kowalczyk and Chad Taylor at Munich’s Olympic Stadium in 2003.

Finally, in 2009, the band and Ed went their separate ways. And it would be another couple of years before they made the decision to carry on without the only singer they’d ever had.

“It took us that long to grow a pair, stand up to all the pressure, and say, ‘no, we’re not doing this – we don’t care if it doesn’t sell.’ And much of the credit for that is for Chris – he’s an amazing singer songwriter in his own right, and he could have come in and said ‘OK, here are the new songs’ but he respected us enough to know we wanted to be a real band again.”

So did Shinn feel the pressure of stepping into Kowalczyk’s shoes as the frontman?

“No, I never looked at it like that,” he says. “I’d worked with people from famous bands before, like Blind Melon and Pearl Jam (in Unified Theory) and worked with Wes Borland – these guys have their way of doing things and I have mine, so you have to make that work for everyone. But we also didn’t want to just pander to what people expect Live to sound like. If we try to second guess what he fans want, that’s defeating the whole object.”

As it turns out though, the resulting debut album from the reborn Live, entitled The Turn, manages to reinvigorate much of the band’s original grunge rock gut-punch with the same life-affirming choruses, offset by tinges of darkness and malevolence, that made their early albums such a riveting listen.

Meanwhile, the obtuse spirituality that characterized Kowalczyk’s lyrics is replaced by startling tales such as Natural Born Killers, which sees Shinn take the persona of a man encouraging his lover to kill her abusive partner so they can elope together.

“I worked on the lyrics with [producer] Jerry Harrison,” Shinn explains. “I imagined a nighttime drive, a love story, when you love someone else who’s in another relationship and trying to tell them it’s fucked up. And Jerry’s like – what if they plot to kill him? And I’m like ‘Now you’re talkin’!’ Aislin Harrison – his daughter, sings on the track, ‘We’re gonna take him down.’”

No references to Eastern philosophy here, but it would surely be a fool who would try to imitate Kowalczyk’s unique (and occasionally bordering on nonsensical) approach.

“I loved Ed’s lyrics, but I have a different approach. The naked Indian’s gone,” says Shinn with a laugh, “But now I feel this is the band I fell in love with again.”

As for Ed, the lawsuits are over and done with, and while the wounds haven’t yet healed fully, his erstwhile bandmates are trying their best not to harbour any ill will.

“I hope some day we can sit down with Ed as friends and reflect on a pretty wild trip,” says Dahlheimer. “Not today, not tomorrow, not next year. But maybe when we’re older and fatter…”

“When you’re kids being in a rock band is just easy, but when you get older and have kids and separate lives you just don’t know the way to give each other the space to grow,” adds Taylor.

“If a band is a marriage, you’re still in a bit in love with that person even after you split. Sometimes the fans are like friends in a marriage who want to take sides. But I want both sides to win. I want Ed to have the solo career he should have had earlier, and I want us to continue with Live in the way we always wanted to.

“The spiritual lesson you take from this is that you have to set each other free. Live took us from young kids in a band at school to flying around the world but it was also entrapping us. We should have let him go but at the same time he should have said, ‘I don’t wanna be in a band any more.’

“Either way, now we feel reborn and we’ve reached a better place. And it feels honest. To make this record all the commercialism had to go – I swear our manager never knew we’d reformed as Live, because we didn’t want that pressure.

“We were back in a little room in York, Pennsylvania, with no air con, figuring how to be in a band again. And the result is that if we never make another record we can hold our heads up and say, ‘this is how rock’n’roll is meant to be.’ It’s real, it’s credible, and it’s honest. It’s Live.”

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.