Ricky Gervais – "At 55 I still have a little bit of punk in me"

The Office star Ricky Gervais on broken rock-star dreams and reviving his David Brent alter ego in a new ‘rockumentary’

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Ricky Gervais has a long-standing relationship with the music industry. From fronting his own short-lived pop duo (Seona Dancing) to managing Britpop stars Suede, to roping in David Bowie for a cameo appearance on Extras, the 55-year-old comedian/actor/director has long had music at the core of his professional life. Now, in his new movie Life On The Road, Gervais revisits his most famous creation, The Office’s David Brent, as the former office manager at Wernham Hogg paper merchants pursues his life’s dream of becoming a rock star, with his band Foregone Conclusion. In Brent’s head, Life On The Road is comparable to Martin Scorsese following the Rolling Stones on tour. “The reality is rather more tragic, but also poignant,” says Gervais. “Not unlike the Anvil movie…”

When did you start planning Life On The Road?

A couple of years ago. When I ended The Office, I said I wouldn’t bring it back. I brought Brent back briefly for a Comic Relief sketch in 2013, and I had to come up with a back story for what he’d be doing now – he’d still be living in Slough, he’d still be repping and dreaming of being a rock star. It’s a staple of comedy to have an ordinary guy trying to do something he’s not equipped to do. And that would have been that, but then I bumped into [former Razorlight drummer] Andy Burrows, and he has a band, and so we did some gigs for fun. And I thought: “If Brent was real, and this former docu-soap star was now trying to be a rock star, that could make a documentary…”

Is there an element in Life On The Road of Marty DiBergi following Spinal Tap?

Of course. This Is Spinal Tap was a big influence on The Office, even though it was about a paper merchants. Christopher Guest [aka the Tap’s Nigel Tufnel] was an influence, with that sort of naturalism, and stupid people saying stupid things but with a straight face. With The Office I tried to take Spinal Tap and make it even more excruciating.

You obviously have a certain amount of sympathy for David Brent. Is that why you didn’t kill him off completely?

Well, you can only disappoint people by revisiting the past. The reason I didn’t want to go back to The Office is because when people say they want a third series, they mean, “I want an episode of The Office I haven’t seen before.” It’s like when a rock star you love brings out a new song, you’re like [shrugs] “Meh”. But when he brings out one and says: “I recorded this in 1973”, you fucking love it, because it’s what you loved about him, and you want to get hold of that again.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

As someone with past ambitions to be a pop star, do you understand Brent’s dream?

Yeah, I do. But I treat it with the cynical eye of a comedian. I think people think I live vicariously through David Brent because I’m a failed pop star but now I get to play at Wembley. And they’re right, in terms of how much fucking fun it is. But the day I release Ricky Gervais Sings The Classics, shoot me. David Brent getting to Number One does not count as me having a Number-One record, any more than [Gervais’s 2008 comedy] Ghost Town gives me permission to be a dentist.

When your own pop career ended did you feel devastated?

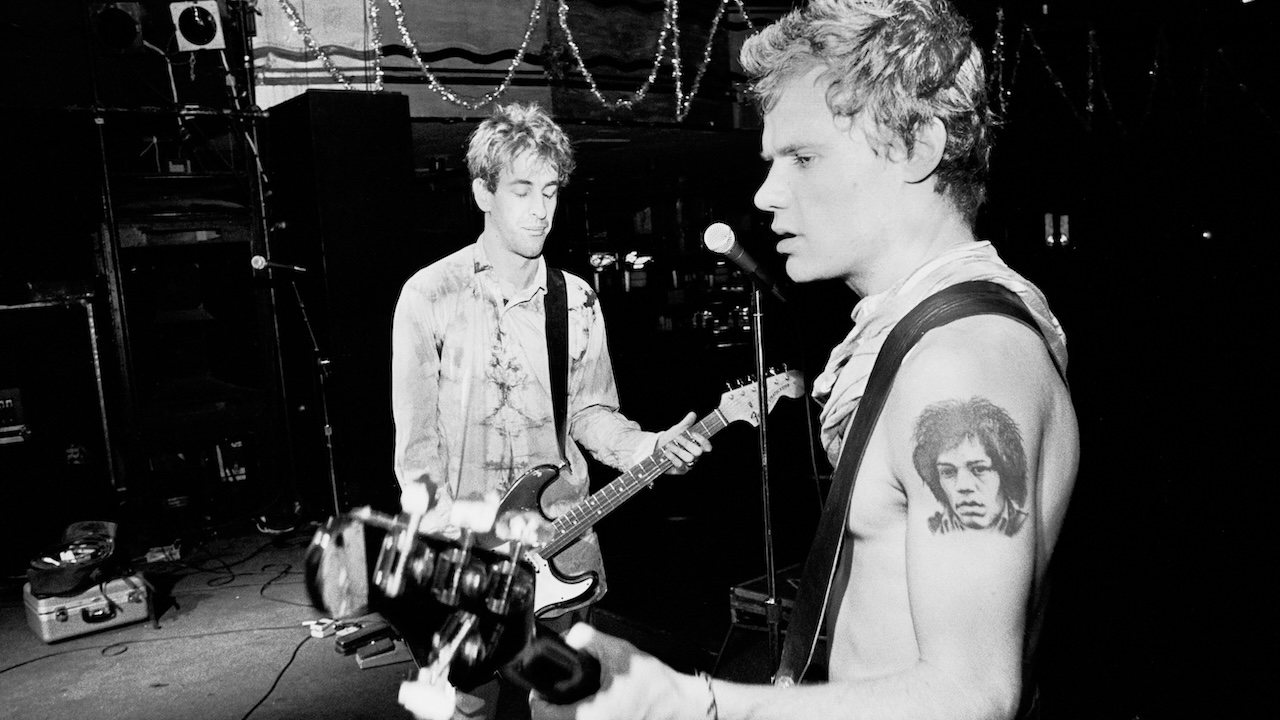

You’re gutted, but you just think, “Okay, I’ll start a new band.” My first mistake back then was wanting to be a pop star. I should have wanted to be a musician. That taught me a lot, because in later life I didn’t want to be a celebrity, I wanted to be a writer/director. People only know I was in a band because I’m famous for something else now, and the video pops up on Graham Norton and we laugh at how thin I was. It was all over very quick. I was signed from a demo, we released a single, didn’t make it, released a second single, didn’t make it, and we were dropped, and that was the end of it. The post-signed years were a bigger influence than the signed years because we played every gig we could get and I invited A&R men to every single one. I remember going to one gig with our equipment in a shopping trolley and the guitarist said, “This is my lowest point ever”. He had a point.

What are your own musical tastes now?

My thing has always been singer-songwriters – Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel. But those artists were handed down to me by older brothers and sisters. But then I discovered Bowie and a whole new world opened up. And then I got into The Smiths and later grunge, while already knowing I was too old. But when I heard Smells Like Teen Spirit I felt the same as when I heard Anarchy In The UK. And then it was Radiohead. The Bends is probably the album I played more than anything. As embarrassing as it might be to say as a fifty-five-year-old, I also love rap, because of its attitude. I still have a little bit of punk in me. I like people being offended by stuff.

In Life On The Road, there are offensive lines in even the sweetest songs, like Don’t Cry It’s Christmas, when Brent sings about Santa visiting a sick child, and points out Santa has one day to deliver gifts, but the kid has slightly less time to live…

You should listen to some real country songs, because they’re fucking tragic! I remember my mum playing Jim Reeves, and there’s one song [The Blizzard] about a guy trying to get home, but in the end his donkey fucking dies in the snow. You think: “Fucking hell!”

You have a guitar chord book coming out for Life On The Road. Is that because you’re secretly quite proud of the songs?

Well I do think we wrote proper songs . But no, it’s David Brent being pompous, explaining songs he thinks are works of art. It’s crucial people understand this isn’t me – this is all David Brent’s vanity project.

You’re still rooting for him though, aren’t you?

It’s like the Anvil movie [Anvil! The Story Of Anvil], if that main guy [frontman Lips] was your brother, what would you do? Would you be all Simon Cowell and say: “You’re never going to make it, stop mucking about,” or do you go, “Good luck,” and go to all his gigs? Probably the latter. Who are we to crush someone’s dreams? Whatever I’ve done, whatever it’s about, I always want to leave both the audience and the character with a bit of hope. Because sometimes hope is all people have got.

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.