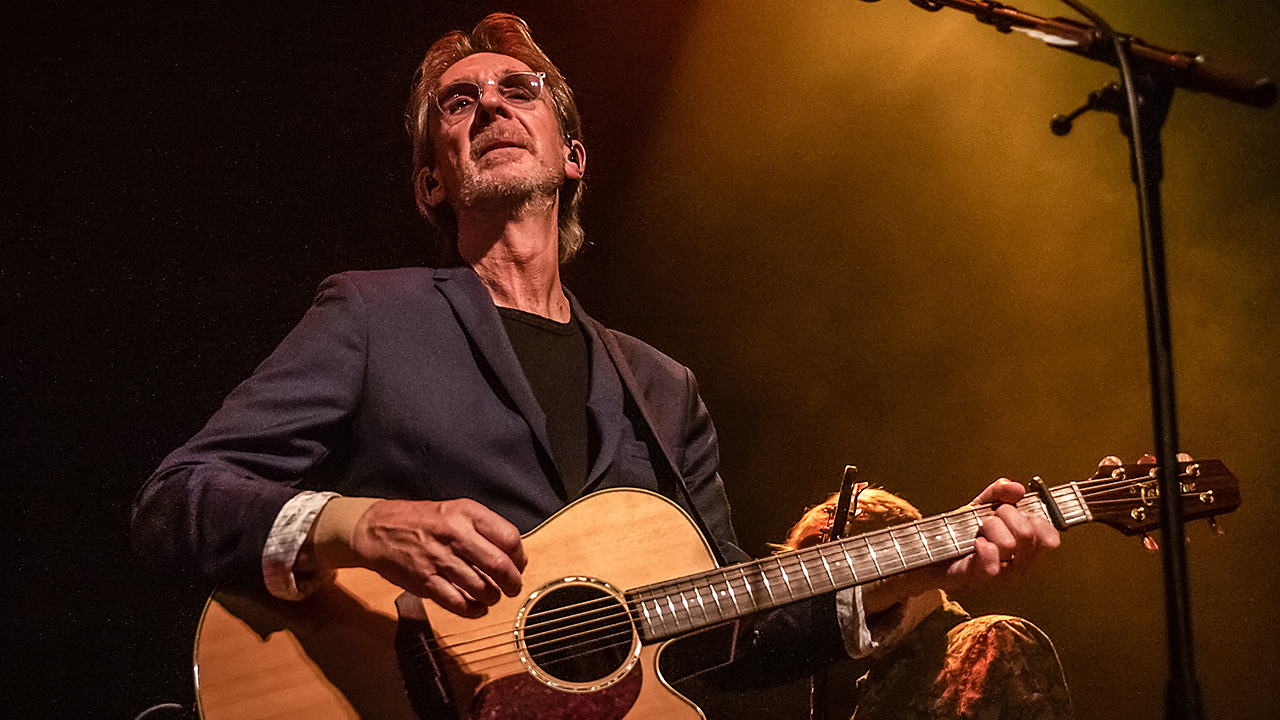

Q&A: Mick Box

The Uriah Heep guitarist remembers fallen friends, taking the denim look to East Germany and the days of sleeping in toilets.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Mick Box, just a few weeks shy of his 68th birthday, is one of rock’s elder statesmen. But the man who formed Uriah Heep in 1969 shows no indication of slowing down. The band have just released a new album, Outsider, full of those textbook Heep motifs: howling Hammond organ, epic harmonies and Box’s breezeblock-sized guitar riffs. “It’s our twenty-fourth,” he says, offering Classic Rock a cup of strong tea in the kitchen of his elegantly appointed North London home. “I think it’s the twenty-fourth.”

Outsider is the first Uriah Heep album since 1985 without bass guitarist Trevor Bolder.

We were waiting for Trevor to get well again, but life took another turn and then he was no longer with us [Bolder died of cancer in 2013]. In the studio we never stopped talking about him as if he was still there. His spirit was there all the way through.

New songs such as the title track and The Law suggest you’ve not gone soft.

Absolutely. There’s still a passion and energy to what we do.

Have you ever come up with a new riff and then suddenly realised: “Oh shit, I’ve written Easy Livin’ again?”

Yeah [laughing]. The first test of a new riff or melody is to do some research. Play it to someone else and ask if they’ve heard it before. It’s the same with lyrics. We’ve actually banned ‘fire’, ‘higher’ and ‘desire’, because it’s too easy to slot them in anywhere.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

You’re the last remaining original member of Uriah Heep. Are you a benign dictator?*

Not a dictator, but I am the driving force. But you have to include all five of the band. We all have to agree on something.

Vocalist Bernie Shaw and keyboard player Phil Lanzon have been in Heep longer than original members David Byron and Ken Hensley were, but do you think they’ll ever stop being thought of as the new boys?

No. They never will. But Heep have a strong history and we have to appreciate that. It’s easy to get trapped, though. We get lumped on to these tours sometimes, and all the other bands are just playing the old stuff – and they’re so lifeless. I keep moving as a writer and musician.

When was the last time you had a ‘proper job’?

In the sixties I worked for an export company in the city. But I told my mum I was going to be a professional musician, and that I’d only do the job for as long as it took for me to pay off the HP instalments on my Gibson Les Paul. Some nights I’d have less than four hours sleep between coming back from a gig and getting up for work. I used to have a kip in the toilets, and my mate would throw a sponge over the cubicle to wake me up if I was needed.

Who inspired your early bands The Stalkers and Spice?

We came out of that Shadows and Beatles thing. But by the mid-sixties it was The Move and The Who. I saw The Who at a pub in London. Feedback was something every other band tried to prevent, but Pete Townshend gave it to you right between the eyes. Hearing that volume made me realise it was time to get a [Marshall] stack.

How competitive were Heep with the likes of Deep Purple?

It was less competitive, more focused on finding your own thing. Purple and Heep both used to rehearse at Hanwell Community Centre. But Purple went down the virtuoso path, and we went for those big harmonies.

Heep have always had a reputation for playing further afield that most bands – Russia, South Korea, India – even in the 70s.

Our motto still is: ‘If they can’t come to us, we’ll take the music to them.’ We played East Berlin in the early 70s. We had denim jackets and jeans on, and people crossed the road just to touch the denim.

What’s the strangest gig you’ve ever played?

A salt mine in East Germany [in 2008]. It was thousands of feet underground, and it took them two hours to ferry the audience in. We also played Rottenburg Prison in Germany.

How excessive did it get for you off stage?

My thing was a drink, and sometimes a little something to keep you awake. I never touched smack, God forbid. But the thing is, I’m a lad from Walthamstow with two feet on the ground. I had my fun, but it never got to a stage I didn’t want it to.

You wore striped trousers in the mid-80s, but were Heep ever tempted to go for the big-haired, Whitesnake look?

Can’t do it, mate [laughing]. It was always music first. I didn’t want to get trapped in an image, and I thought when I get older I don’t want to be doing this with piled-up hair and make-up.

Do you have any regrets from Heep’s 45-year career?

Of course. Losing David [Byron, original vocalist, who died of liver disease in 1985] and Gary [Thain, bassist, who died after a heroin overdose in 75]. There was no education about drugs then. People popping their clogs was the wake-up call. Also, being in this business is not always conducive to a happy home life.

What do you do when you’re not Mick Box of Uriah Heep?

Football and family. I’m a Spurs supporter, for my sins. But after months of being cooped up in vans, cars and planes, it’s lovely to take off the rock’n’roll hat, put the dad hat on and stand on the touchline watching my 13-year-old son playing football or rugby.

When you were sleeping in that toilet cubicle, could you have imagined still being a professional musician 50 years later?

Never. But it comes down to good songs. I’m also a born fighter. Believe me, I don’t give up easily.

Outsider is out now via Frontiers and is reviewed here.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.