New Horizons: Mike Vernon (Part One)

Part one of our Mike Vernon celebration

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Without producer and label boss Mike Vernon, the history of British blues would look very different. In the first part of a feature charting his career, he opens his photo archive and takes us back to the start of Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and David Bowie…

British blues would be far poorer without Mike Vernon. As both a major-label producer and founder of Blue Horizon, the country’s leading blues label of the 60s, he helped shape the careers of such luminaries as Eric Clapton, John Mayall, Ten Years After, Savoy Brown and Chicken Shack, though perhaps his most crucial alliance was with Fleetwood Mac, led by the inimitable Peter Green. Under Vernon’s tutelage, the band graduated from blues boom heroes to million- selling superstars.

In his recent memoir Play On: Now, Then And Fleetwood Mac, Mick Fleetwood says Vernon “deserves tremendous kudos for his guidance, not only in our career, but for many others in the English blues scene too. He did more than anyone knows to further the music and nurture the artists.” Factor in the producer’s involvement with Graham Bond, Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Duster Bennett, Rory Gallagher, Paul Kossoff and Mick Taylor and you start to appreciate where Fleetwood is coming from.

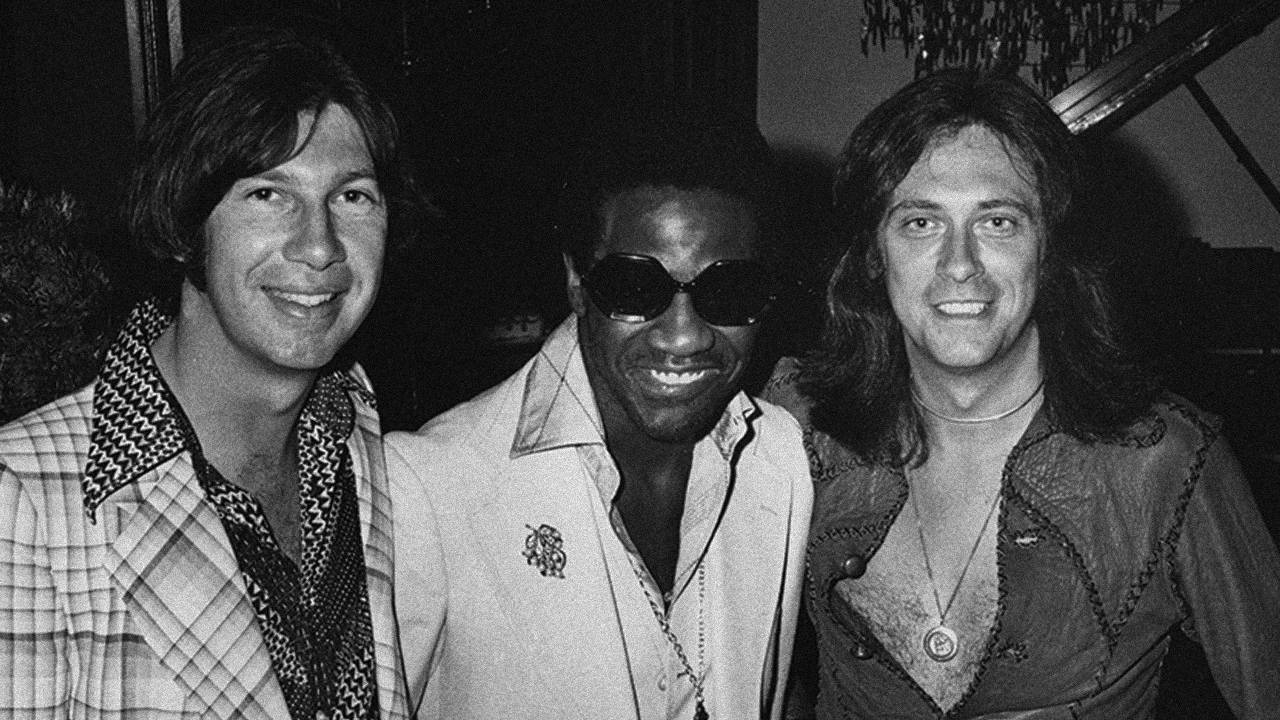

Vernon would be assured legendary status were it only for the above. But, over a working life that’s endured for over 50 years, he’s also recorded David Bowie, Focus, Bloodstone, Dr Feelgood and a whole host of American figures. These range from the relatively obscure (Johnny Shines, Curtis Jones, Mississippi Joe Callicott) to the semi-mythical (Champion Jack Dupree, Freddie King, Otis Spann, Hubert Sumlin, Willie Dixon).

The 70s saw Vernon issue a couple of solo albums under his own name, as well as form a part of two successful, highly contrasting bands: The Olympic Runners and Rocky Sharpe & The Replays. He went on to produce yet more artists and start up other labels – Code Blue among them – before giving it all up and moving to Spain at the turn of the millennium. It would be another 10 years before he was coaxed out of retirement.

Vernon’s return to work was fairly low-key, producing albums for British blues prodigies Oli Brown and Dani Wilde. But both experiences left him eager for more, to the point where he now has several projects in the air. The most recent is Just A Little Bit, which finds him fronting his own band, The Mighty Combo, and revisiting the music that first fired his imagination. Given the fact he began as a singer with The Mojo Men, you can’t escape the feeling that Vernon is squaring a very large circle.

“I suppose you could put it that way,” he says, down the line from his home in Andalucía. “The original plan was to do about six tracks, but somehow it grew and grew until it was like a runaway train. I couldn’t stop it. It ended up being my own personal homage to all the great singers, songwriters and labels of the 40s and 50s that got me into the blues in the first place. It’s been getting some very good reactions. In the early days I was frightened to death whenever I got up on stage, though now I’m completely the opposite. Fifty-plus years of being in the music industry knocks all that out of you.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

This last sentence is accompanied by a chuckle, but there’s enough dryness in there to suggest that Vernon is only half-joking.

Over the next two-and-a-half hours, which slip by like a solo from Peter Green or Freddie King, Vernon takes The Blues on a journey through his past. And, by correlation, that of the British blues scene itself. He’s well prepared too, he explains, having dug out a personal discography that’s as near as damn it to comprehensive. Yet despite the benefit of this epic chronology, it transpires that there are still gaps in the details, mostly due to the sheer volume of sessions that Vernon has been involved in.

Like many of his contemporaries in post-war England, Vernon’s portal to the blues was radio. Born in Harrow in 1944, but raised in the suburbs of Croydon and Kenley – then both still part of Surrey – he began devouring music while at grammar school. “It became the norm to listen to stations like Radio Luxembourg and AFN,” he recalls. “I’d get those on my Bakelite Echo radio and listen to the music under the bedclothes way past midnight, which was when all the good stuff got played. In those days nobody ever referred to it as rhythm and blues – it was rock’n’roll: Fats Domino, Little Richard, Wynonie Harris. It wasn’t until I got introduced to the people at Blues Unlimited magazine – Simon Napier, Mike Leadbitter and John Broven – that I realised this was just a spin-off from what had originally been referred to as ‘race music’. That was when I started to dig into the background of it all. Most of the artists I’d been listening to were black and it suddenly made me realise that my ties to the blues were very real. I’d actually been listening to rhythm and blues records without knowing it. Then I started to discover the obvious culprits: Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Josh White, Memphis Slim. And that’s where it all really started.”

Vernon’s problem, however, was the same as that of other young converts to American blues: how to get hold of the records. There were next to no outlets on the high street and the big labels didn’t appear to cater for blues at all. “It was nigh impossible,” he admits. “Initially, only one or two companies released any kind of blues product. The most successful one, in terms of making those records available, was Decca, through the London America label. But it was Mike Leadbitter, the champion of the down-home blues stuff and music from New Orleans and Chicago, who turned us on to the guy who could get them from America by mail order. My brother [Richard] and I, and my school buddy Neil Slaven, used to go down to Bexhill-on-Sea and meet up with these guys and spend the whole day there, listening to nothing but 45s and 78s. That was my education in the music. Then I started to get involved in what was going on in London and had many more opportunities through people like Guy Stevens and Paul Oliver, Derrick Stewart-Baxter and Max Jones. They were the main players.”

My ties to the blues were very real. I’d actually been listening to rhythm and blues records without knowing it.

In the wake of Vernon’s exposure to these blues writers and authorities, he started up a fanzine with his brother and Slaven. The first edition of R&B Monthly was duly published in February 1964, by which time Vernon was a regular visitor to London’s blues clubs and had already been working at Decca for over a year. “I’d started writing all these pleading letters to record companies and one of them led to me being invited for an interview there. I started work at Decca in November 1962, at the tender age of 18, as an assistant to the head of A&R, Frank Lee. I answered the phones, made tea, ran errands – the whole bit. But at the same time I learned the ins and outs of the music industry. It was a very valuable insight. I used to go to the studios in West Hampstead and work as Frank’s assistant. It was boring orchestral stuff mainly, people like Mantovani, Frank Chacksfield and Gracie Fields. Gradually I progressed to a would-be producer.”

Vernon reels off a bizarre list of acts he was asked to oversee at Decca, including the Zbigniew Namyslowski Modern Jazz Quartet and Austro- Polish pianists Rawicz and Landauer (“I did an album with them called Rawicz And Landauer Play South African Favourites. How niche is that?”). As a measure of his eclecticism, he also did tape editing for Spike Milligan and Benny Hill.

Vernon is, however, very keen to point out that his first real credit as “a legit producer” was in 1963 for The Yardbirds: Baby What’s Wrong and Honey In Your Hips. Co-produced with the band’s manager Giorgio Gomelsky, this in turn led to other jobs that were more attuned to his own tastes. Later that year he auditioned Spencer Davis’ Rhythm & Blues Quartet (“with a 14-year-old Steve Winwood”), but his Decca paymasters rejected the band.

A similar fate befell The Graham Bond Organisation, in whose ranks were future Cream stars Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker: “They did stuff like Long-Legged Baby, Wade In The Water and High-Heeled Sneakers. Not long after, Decca changed their mind about them and, in May 1964, I produced the GBO’s Long Tall Shorty.”

Vernon also recalls an audition with The Groundhogs, who were then known as John Lee’s Groundhogs (after John Lee Hooker), featuring Tony McPhee.

The roots of Blue Horizon, meanwhile, can be traced back to a humble home recording that Vernon made in November 1964. Howlin’ Wolf and his trusted guitarist Hubert Sumlin were touring Britain on a package that included Chris Barber’s Blues Band and Long John Baldry.

“Neil Slaven and I had been talking about the possibility of having a record label since we started R&B Monthly,” Vernon says. “We befriended Hubert during the tour and explained that our plan was to start a record label called Blue Horizon and that we’d like to launch it with a couple of instrumentals from him. He said, ‘Great idea. Where are you going to do it?’ I told him that if he fancied a drive into the English countryside on his day off, we could talk about it. We drove him down to my parents’ house on Godstone Road in Kenley, where I had a Grundig three-speed tape machine. We just plugged him into an amplifier my dad had made for my record deck and recorded Hubert in my bedroom. That’s how Blue Horizon Records started.”

Vernon and Slaven cut five songs with the guitarist during that session. Two of them, Across The Board and Sumlin Boogie, came out in early 1965 as a limited-edition mail order release of just 99 copies.

Vernon’s workload at Decca, meanwhile, was throwing up some fascinating opportunities. The previous summer had seen him make The Blues Of Otis Spann, in his opinion “still one the greatest blues records ever made”. The studio line-up wasn’t bad either. Alongside Muddy Waters, Ransom Knowling and Little Willie Smith, Vernon had roped in 20-year-old session player Jimmy Page and teenager Eric Clapton, then with The Yardbirds. In his self-titled autobiography, Clapton calls it an example of the “incredible life” he was starting to lead. “I was absolutely terrified,” he writes, “not because I felt I couldn’t carry my weight musically, but because I didn’t know how to behave around these guys. They had these beautiful baggy suits on and were so sharp, and they were men, and here I was, a skinny young white boy.”

Alas, the song on which Clapton played lead, Pretty Girls Everywhere, failed to make the final cut.

It wouldn’t be long, however, before Vernon and Clapton crossed paths again. John Mayall and his Bluesbreakers had made their Decca debut with a live album – the imaginatively-titled John Mayall Plays John Mayall – in March 1965. Vernon had seen the Bluesbreakers on a number of occasions around London, but it wasn’t until Clapton replaced guitarist Roger Dean in April that year that “it became a completely different project.

I was so impressed by John’s band once Eric joined. The whole feel was different and I have to say that Eric’s playing with The Yardbirds was a shadow of the way he played with John Mayall. It was obvious that he wasn’t allowed any freedom whatsoever with The Yardbirds. They just did uptempo stuff to facilitate Keith Relf’s desire to do Jimmy Reed-type material. It certainly wasn’t that big fat sound that Eric got once he joined John. I moved in on John and Eric in February 1966, when I asked them to be part of Champion Jack Dupree’s From New Orleans To Chicago album. They both came and played on that, along with people like Keef Hartley and Tony McPhee. That experience led to me reintroducing Decca to John Mayall.”

Clapton had left the Bluesbreakers without warning to travel around Europe the previous summer, only rejoining the fold in problems you have when faced with a guitarist November ’65. Mindful that it was probably now or never, Vernon set about persuading Decca boss Hugh Mendl to allow him to hustle the band into the studio as soon as possible. Sessions for Blues Breakers, billed as John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton, were arranged for April ’66 at the label’s facility in West Hampstead. The remainder of the band, incidentally, consisted of bassist John McVie and drummer Hughie Flint.

The directive was to capture the rawness of the Bluesbreakers’ live shows, where they were accustomed to playing pure blues at a searing volume. This turned out to be problematic for Vernon and engineer Gus Dudgeon. “For me and Gus, it was an introduction to the enormous problems you have when faced with a guitarist who’s playing as loud as Eric,” says Vernon. “We’d never really come up against that before. The studio was only medium-sized, maybe 30 by 25 yards, and the big problem was that the band members wanted to have proximity to each other. They wanted to be almost physically able to touch each other. Eric wanted to be able to feel his amp. He said, ‘The only way I can feel it is to stand in front of it.’ So we had to find a way and it was very hard work. Immediately in front of the window was John, with his organ and harmonica set-up. And Eric stood in front of the amp, which had baffling carpeting and even the piano cover over it. At the end of the day we just basically said, ‘Fuck it! We’ll just have to record it the way it is.’”

The resulting album was a landmark in British blues. Clapton has cited its “raw, edgy quality” as the thing that made it special, while on a personal level, it also heralded the start of his signature guitar sound. The songs, a mixture of standards and originals, were delivered with breath-catching verve and assurance, sizzling from the speakers with such force that it made most of their contemporaries sound limp.

The album was also notable for Ramblin’ On My Mind, which featured the first solo lead vocal of Clapton’s career. “He needed a lot of convincing to do it,” Vernon recalls. “It was John’s idea and there was a real reticence. Eric was going: ‘I’ll be honest, I’m not really a singer.’ He kept trying to wriggle out of it, but John would say: ‘No Eric, you have a great voice. I think it’d be great for the record.’ So he reluctantly agreed and it proved the point.”

Blues Breakers was an introduction to the enormous problems you have when faced with a guitarist who’s playing as loud as Eric Clapton.

The suits at Decca had so far been unyielding when it came to the blues, refusing to view it as a viable commercial option and thus showing no interest in its promotion. But this was blues with a new sense of lust and vitality, proclaimed by the hottest young guitarist in England. Vernon recalls: “When the album went to No.1 on the Melody Maker album charts [it reached No.6 in the national Top 40], Decca couldn’t believe it. Nobody could. But it improved my standing instantly. From that moment onwards everyone paid attention. If I told them that I had an opportunity to sign a new blues-based band, they all went, ‘If you think so, go ahead. Do it.’ Before that, all they did was reject everything.”

It’s to Vernon’s undying amusement that he followed up Blues Breakers with one of the unlikeliest projects he could envisage. Still prey to the whims of his Decca chiefs, he was tasked with recording the Spanish duo of Don Pedro and Don Jose. “It’s bloody awful. I don’t know how I got to even make that record. It’s called Cumbia Del Sol and is one of those terrible things you hear in Torremolinos when you’re eating paella and two guys come up and start singing these rubbish songs.”

He also recorded The Artwoods (featuring future Deep Purple organist Jon Lord), folk singer Paul McNeill and a young David Bowie in ’66 (see panel). But it was a swift reunion with John Mayall that provided the impetus for the next phase in his professional life. Scheduled to oversee a new Bluesbreakers album in October, Vernon walked into the studio to find Clapton gone. In his place was a young guitar player he didn’t recognise. “Don’t worry,” assured Mayall, noting Vernon’s shocked expression. “We got someone better.”

Vernon was thus introduced to Peter Green, who’d just left the employ of future Camel keyboardist Peter Bardens in Peter B’s Looners. “To be truthful, I wasn’t really aware of the existence of Peter Green up until that particular moment,” concedes Vernon, “though I think I’d actually seen the Looners play the Flamingo as a support act.”

It wasn’t long, however, before he understood what Mayall was talking about. As the sessions for A Hard Road progressed in West Hampstead, Vernon observed that Green had a very different style to Clapton, though with the same drive and conviction. “I thought he was going to be a clone of Eric, but he wasn’t. I should’ve had wider vision. Eric was quite definitely a Freddie King disciple, even though there were people like BB King and Matt Murphy that he was also listening to. Whereas Peter was much more of a BB King devotee and also had a different touch in his playing. He poured out his heart and soul through his fingers and there was a different sound, quality and atmosphere about his notes that made him individual. It wasn’t until we got into making A Hard Road that I realised exactly how lyrical he was as a player. That lyrical element was far superior to Eric’s at that time. There was something about the way he played that just tugged at your heartstrings. He was really wonderful to listen to.”

A major highlight was an inflamed version of Freddie King’s The Stumble, with an astonishing Green solo. And while the bulk of the songwriting was taken on by Mayall, Green – who also sang lead on two tunes – contributed a couple of his own.

One was The Supernatural, a striking instrumental that carried a pre-echo of his work with Fleetwood Mac: extended notes, trademark sustain, a rare tone and fluency. “The Supernatural was basically made up in the studio,” remembers Vernon. “None of it was pre-written or planned. Peter and I talked through the idea of doing an instrumental with an Otis Rush feel to it, in a minor key with some kind of melody. And lo and behold, that’s how it materialised. In a way it set a precedent for what Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac would end up being.”

Released in February 1967, A Hard Road followed its predecessor into the Top Ten of the UK charts. Not that it mattered much to Green, who was already itching to move on. “John was the leader of the band and wanted things done his way,” Vernon says. “There were limitations in the Bluesbreakers: you were allowed to express yourself, but you weren’t allowed to take over.

And that’s the sign of a good bandleader, which John has proved to be over the years. But Peter wanted to do something of his own.”

The Bluesbreakers’ most recent addition had been drummer Mick Fleetwood, who’d also played with Green in Peter Bardens’ band. When it came to starting up his own outfit, the guitarist naturally reached out. Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac were thus formed in July ’67. And while John McVie, their ideal choice for bassist, wavered between a steady pay cheque with the Bluesbreakers and the enticement of a new band with his name already incorporated into the title, Green recruited Bob Brunning and slide guitar player Jeremy Spencer. Both of them had prior form with Vernon at Decca.

“Somebody had recommended that I should check Jeremy’s band out,” Vernon recalls. “They were called the Levi Set Blues Group, from Lichfield in Staffordshire. I organised a Decca demo session for them and they weren’t very good, though Jeremy was great. The music didn’t swing or rock and it was very untidy. So I didn’t even take it to anyone at Decca. Then around the same time Peter mentioned to me that he was thinking about leaving John Mayall and forming his own band, I passed him the information about Jeremy. It turns out that they did a gig as John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers somewhere near Lichfield, and Jeremy’s band were either the support or Jeremy went to the gig and introduced himself to Peter.”

Peter Green poured out his heart and soul through his fingers.

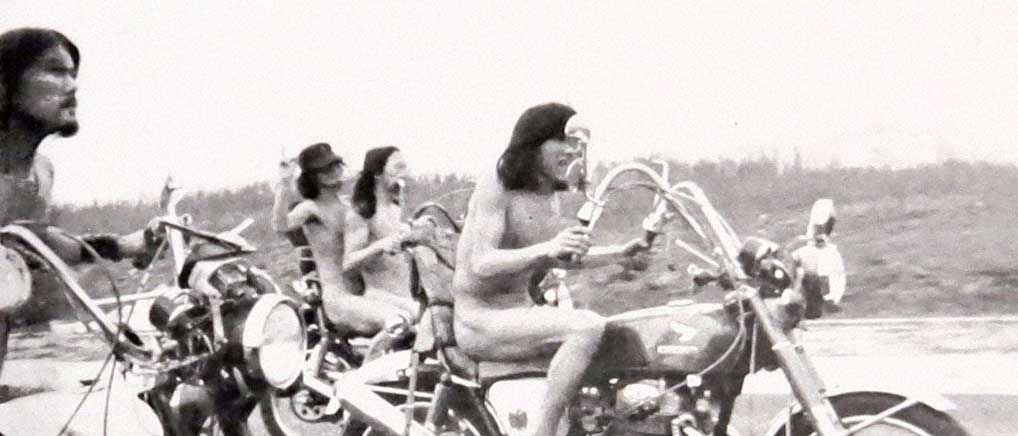

Green’s Fleetwood Mac made their debut at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival in August. Sharing Sunday’s bill with Cream, Jeff Beck, Donovan and John Mayall himself, they were an instant hit. “They played that festival and completely blew everybody away,” says Vernon. “From that moment onwards there was no stopping them.”

Green was also eager to retain Vernon’s services in the studio, telling the producer he wanted to release records on Blue Horizon. “My very first attempt at recording the band were two instrumentals called Fleetwood Mac and First Train Home, in August 1967, with Peter Green, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood, which was going to be the original format. However, on September 9, 1967 we recorded I Believe My Time Ain’t Long and Rambling Pony, which became the very first commercial Blue Horizon single via CBS. That line-up was Peter, Mick, Jeremy Spencer and Bob Brunning. That’s when the label really started.”

He’d initially offered the demos to Decca, but they refused to license and distribute them on Blue Horizon. CBS, on the other hand, had no such issues. As a consequence, Vernon was summoned to a meeting of the top brass on Decca’s seventh floor. Ill-disposed towards the producer’s new endeavour, they told him that he couldn’t produce records for rival companies Vernon was slapped with an ultimatum that amounted to the same thing: either quit or get fired. He promptly resigned on the spot. Three weeks later, once relations had thawed a little, he returned and signed an independent production deal with Decca, which allowed him the best of both worlds.

The whole of 1967 had been a busy time for Vernon. Among other album projects, he recorded Savoy Brown (Shake Down), the self-titled debut from Alvin Lee’s Ten Years After, Champion Jack Dupree & His Blues Band and two further LPs from John Mayall (solo effort The Blues Alone and, with the Bluesbreakers, Crusade, featuring an 18-year-old Mick Taylor). But Fleetwood Mac, who also doubled as Blue Horizon’s resident house band, rapidly became his main focus as the year wore on. Over a three- week period in November and December, Vernon ushered them into CBS Studios and bottled the essence of their live set.

The resulting LP, simply christened Fleetwood Mac, drew both from Spencer’s Elmore James fixation and the BB King-styled expressionism of Green. Aside from a sprinkling of covers, the songwriting was roughly split between the two, though it was ultimately Green’s compositions that shone brightest, particularly the spicy Long Grey Mare and the pining beauty of I Loved Another Woman. Green also revealed himself to be a sensitive, if unspectacular, vocalist, his lack of American mannerisms adding a very British sense of bluesy authenticity.

“It’s interesting how the dynamic panned out,” opines Vernon, “because one would’ve thought that taking on Jeremy Spencer was probably the worst thing Peter could’ve done. Jeremy was such a diehard Elmore James soundalike that in a way it took the music in the opposite direction for Peter. But he actually made it work, because now they had two guitarists who were completely different but could back each other up. When Jeremy did his Elmore stuff, Peter was the perfect rhythm player. He would do exactly what was required. Then when Peter came to do his things, Jeremy either did the absolute bare necessities or didn’t play at all. Or he’d occasionally play piano.”

Issued in February ’68, Fleetwood Mac was a commercial hit, peaking at No.4 in the UK album charts, where it hung around for the best part of a year. Black Magic Woman, not included on the LP, was released as a single in March and provided the fullest indication yet that Green was a gala talent. Building on the Latino flavour of I Loved Another Woman, the song was a majestic communiqué that gave the band their first Top 40 single. It would also become an enormous success in the US, when Santana covered it two years later.

It also marked the onset of Green’s ambiguous relationship with mainstream stardom. “Black Magic Woman was the beginning of a new career for Peter,” says Vernon. “He didn’t want to be a rock star at all. That was a big issue for him. He was just a quiet, ordinary Jewish lad who played guitar. Yet at the same time he couldn’t live without playing and the band became enormously popular. It was almost like overnight success.”

For better or worse, Fleetwood Mac were about to become bigger than any of them could imagine.

How Mike Vernon kickstarted David Bowie’s career…

Aspiring pop star David Bowie was going nowhere. After three failed singles for Pye, manager Ken Pitt arranged a meeting with Hugh Mendl, head of A&R at Decca subsidiary Deram, in October 1966. The 19-year-old Bowie was duly assigned Mike Vernon as producer of his first LP.

“Hugh Mendl had artists like Julie Felix and Anthony Newley, which was probably why I got the David Bowie job,” says Vernon. “I think Hugh took a liking to him because he sounded like a young version of Anthony Newley. I just thought it was an interesting project, but I have to admit that I never really understood what it was all about.”

Bowie’s material was still years away from the glam’n’roll of his Ziggy Stardust persona. Instead, his preoccupations were traditional English music hall and whimsical rhymes about parochial life, peopled with gravediggers, old maids and giggling gnomes. “It was like poetry, but set to music. And sometimes it was more of a semi-spoken thing. It was just odd, with a very strong theatrical element. My only concern during the making of the album was that I couldn’t get to grips with who was going to buy it. Then when David started doing The Laughing Gnome, he said, ‘I’m making this for kids. They’ll love this!’ It was like an English spoof of The Chipmunks.

“For me,” Vernon continues, “the one really successful recording that Bowie and I did together was Love You Till Tuesday, which I thought was really fabulous. We got a full orchestral sound and it had a real commercial feel. It very nearly made the charts, but didn’t quite get there.”

Indeed, as Melody Maker’s guest reviewer Syd Barrett commented in May 1967, the single was “very chirpy, but I don’t think my toes were tapping at all”.

Issued on the same day as The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper…, Bowie’s self-titled debut stiffed completely. As did its two singles and novelty 45, The Laughing Gnome. Two years later, however, he hooked up again with Vernon’s engineer, Gus Dudgeon, and recorded Space Oddity. The song was a huge hit. “He and Gus got on really well together when we did the album and it’s no surprise that they carried on building a working relationship. Gus was a great person to bounce ideas off and had plenty of his own.”

Vernon was also to taste success with Bowie, albeit after the fact. In 1973, with Bowie now the hottest ‘new’ talent in British rock, a reissue of The Laughing Gnome made the Top Ten, sell a quarter of a million copies.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.