What happened when Joe Strummer drank 10 pints of beer then ran the Paris Marathon

In 1982 The Clash's Joe Strummer disappeared without telling his bandmates, his manager or his record label. Then he got drunk and ran a marathon

In the spring of 1982, The Clash were starting to come apart at the seams. The strain between guitarist Mick Jones and the rest of the band was compounded by drummer Topper Headon’s debilitating heroin problem.

Rather than confront the problems, frontman Joe Strummer decided to take drastic action by taking off to Paris without telling his bandmates, his manager or his label, CBS. The media speculated that it was a publicity stunt put together by the band’s manager, Bernard Rhodes, to promote their soon-to-be-released new album, Combat Rock, and the subsequent tour.

Little did anyone know that Strummer was about to gatecrash the Paris Marathon.

Topper Headon (drummer, The Clash): It wasn’t a very happy band at that time. I was addicted to drugs, out of my head all the time. As well as that, Mick was behaving like a rock star, and we’d all lost sight of what we’d set out to do in the first place.

Bernard Rhodes (manager, The Clash): Joe had a lot of personal problems, okay? And I told him: “Take a break”. He was gonna go on a big tour and I didn’t want that hanging. I told him to go and sort it out.

Joe Strummer: I just got up and went to Paris without even thinking about it. I might have gone a bit barmy, you know? I knew a lot of people were going to be disappointed, but I had to go.

Kit Buckler (Head of Press, CBS Records): I’d known Joe for years, from the days before he was even in a band, when we shared a squat in Kilburn. But when he vanished, none of us had a clue where he was.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Topper Headon: Mick, Paul and I were completely in the dark, no idea where he’d gone.

Steve Taylor (journalist, The Face): [After spotting Strummer on a night train to Paris] Joe was looking tired, wearing shades, travelling light and consulting a cheap paperback guide to Paris. It looked like he was planning to stay in the city.

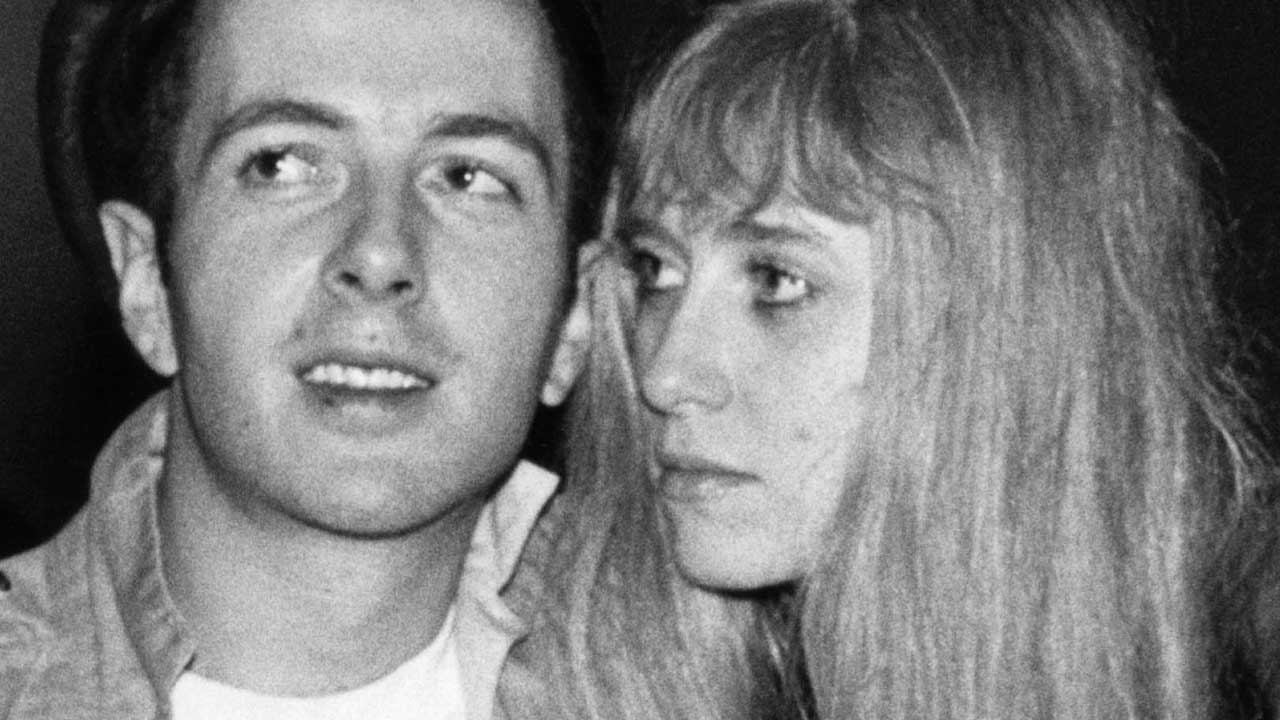

Richard Schroeder (Parisian photographer): When Joe and his girlfriend Gaby Salter got to Paris they immediately lost their passports and all their other documents. The only person they knew in Paris was a friend of Gaby’s daughter who had a small flat in Montmartre, so they stayed with her.

Fortunately, she knew I was a big fan of The Clash, and of Joe, so she called me and said: “Come over tonight. I have a surprise for you”. When I got to her flat, there was Joe and Gaby. And we got along very well from the start. We were the same age, so it was great.

Joe Strummer: I only intended to stay for a few days, but the more days I stayed, the harder it was to come back, because of the more aggro I was causing that I’d have to face.

Richard Schroeder: Joe and I saw each other almost every night for the next three weeks. We would meet, have dinner somewhere, and then we’d visit maybe 10 bars every night, drinking, and talking, talking, talking about how to make the world better. It was very simple. Most of the places we went were in the Pigalle.

We went, I think, a few times to the Noctambule. Joe liked that place because in the back room there was an old guy who sang French chansons from the old days, and Joe loved that. One thing that surprised me was that no-one recognised him. The Clash were huge in Paris, but no one came up to him. He was growing a beard, so maybe…

Kit Buckler: Once word got out that he’d vanished, it became a huge front-page story in the media, which we had to deal with quickly because the album was about to come out. We were dealing with two main people in the Clash camp: their manager Bernard Rhodes, who was always trying to poke the hornets’ nest, and their other right-hand man, Kosmo Vinyl, who was the one who poured oil on troubled waters.

Topper Headon: The story that went out was that tickets for the tour were not selling well in Scotland, so Joe and Bernie hatched this plan for Joe to disappear to Paris. It never made any sense to me. If Joe went missing, how was that going to sell tickets in Scotland?

Kit Buckler: There had been a bit of an atmosphere within the band. They weren’t talking to each other during rehearsals and so on. Bernard was always irrational, difficult to work with, the master of post-rationalisation, and my take on it is that that’s where the scam/publicity story thing came from. Bernard saw what was going on and realised he could make something out of it.

Richard Schroeder: The official version was, like, they had to make an event to create publicity which would help to sell more tickets. But Joe never mentioned that to me. What he told me was that it was mainly the drug problem with Topper. So it was more about the problems with the band, and Joe wanted to be out of that for a while, to have a chance to think about it properly.

Bernard Rhodes: Joe going to Paris had nothing to do with ticket sales. Where the ticket sales thing came in, I do not know.

Kit Buckler: After the furore had started – and there were even rumours that he’d committed suicide – I remember Joe ringing me in the CBS press office and saying: “Don’t worry, I’m all right. I just felt I had to get away”.I think things had got on top of him. He was finding the pressure suffocating. Joe didn’t like using the phone, so it probably took a lot for him to call me, and he intimated that he wouldn’t be gone forever.

Richard Schroeder: Near the end of his time in Paris, Joe bought a French newspaper, because he wanted to learn French, which he never actually did. We met in a bar and he was reading in the newspaper about the Paris Marathon. “Oh, there’s a marathon on Sunday. Do you think we can do it?” I told him I didn’t know how to enter it. He said: “Yeah, but if we just turn up on the day…” I told him he was in no shape to run the marathon, but he said that being on stage was like sport.

A post shared by British Culture Archive (@britishculturearchive)

A photo posted by on

Kit Buckler: You’d never know it to look at him, but Joe was a reasonably heathy guy. We used to play five-a-side football in-between Clash recording sessions at Westbourne Grove, and he was pretty good. He had previously run at least one marathon before he went to Paris, and he ran others after he came back.

Richard Schroeder: He made no preparations for it. He didn’t do any training. The day before the marathon he was completely drunk.

Joe Strummer: You really shouldn’t ask me about my training regime, you know. Okay, you want it, here it is: drink 10 pints of beer the night before the race. Ya got that? And don’t run a single step at least four weeks before the race… But make sure you put a warning in this article: ‘Do not try this at home’. I mean, it works for me and Hunter Thompson, but it might not work for others. I can only tell you what I do.

Richard Schroeder: So, anyway, we borrowed some shorts and running shoes and I took them to the start. I left them there and told them I would meet them at the end. Which was about three hours later. Gaby didn’t do the whole marathon, she abandoned before the end. So I met her at the end, and we waited together for Joe to complete it.

He always said he took about three hours 20, but I think it was more like four hours. Hundreds of people came past and then we just suddenly saw Joe. He was completely exhausted. There was a big table with water and orange juice and sugar cubes and this sort of thing for the runners. Joe fell into my arms, and I asked him: “Do you want some orange juice?”. He said: “I want a cigarette and a beer”.

I took a few photographs in which he’s wearing my jacket and you can see the beer in his hand and he has the medal round his neck. Everyone who completed the marathon got the medal. And he was really proud of it.

So I took them back to the flat and I assumed we wouldn’t see each other that night because he’d need to sleep, but he called me at midnight and said: “Hey, d’you want to have another few beers?”. The next day, Joe couldn’t move. He was walking around like a 90-year-old man.

A post shared by La Galerie du Rock (@lagaleriedurock)

A photo posted by on

Frank VanHoorn (promoter, Lochem festival): A journalist I knew spotted Joe in Paris and rang me up because he knew I was anxious about whether The Clash would make it to my festival. So I rang The Clash office in London and told Bernie.

Joe Strummer: They hired a private detective to find me.

Richard Schroeder: The story I heard was that there was a private detective who was called in who tracked Joe down, and then Kosmo was sent over to Paris.

Kit Buckler: That’s right, it was Kosmo who was sent to track him down in the end.

Richard Schroeder: I think it was two days after the marathon that Kosmo Vinyl arrived and found him and convinced him to go back to London. Joe called me up and said: “They found me!”, but he was laughing about it.

Kit Buckler: I think Joe was ready to come back. There was this dichotomy with him… He did have these periods over the years where he would cut himself off and become quite isolated, but the next time you saw him he’d be the wonderful, warm guy that he usually was. I think he’d have come back even if Kosmo hadn’t gone and found him.

Richard Schroeder: He knew he would have to come back, because the tour was coming up. He said: “We have to go back, but let’s meet up because there’s someone I want you to meet”. That’s when I met Kosmo, who was not very nice to me at all. He thought I was part of the problem, that I was the one who was hiding Joe in Paris.

Frank VanHoorn: Their first gig after Joe was discovered was my festival, which they were headlining. They played great, but Topper seemed to be in a bad way.

Topper Headon: I found a letter that I wrote at the time to Joe about his disappearance, and in the letter I say: “I understand your unhappiness with the way the band is”. I admitted I wasn’t getting on with Paul, and it was all pretty chaotic. I was saying that if he came back I’d get my act together. But of course I never sent it to him, because we had no idea where he was.

Richard Schroeder: It was a very special time for Joe and Gaby, the first time they were away from everything and they were just being tourists. They loved it. Gaby later told me that those were the three best weeks she ever had with Joe. She said it was like a dream because there was just the two of them. Usually Joe never had a day free.

Joe Strummer: It was something I wanted to prove to myself: that I was alive. It’s very much like being a robot, being in a group. You keep coming along and keep delivering and keep being an entertainer and keep showing up and keep the whole thing going. Rather than go barmy and go mad, I think it’ better to do what I did, even for a month.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 194, in March 2014

Johnny is a music journalist, author and archivist of forty years experience. In the UK alone, he has written for Smash Hits, Q, Mojo, The Sunday Times, Radio Times, Classic Rock, HiFi News and more. His website Musicdayz is the world’s largest archive of fully searchable chronologically-organised rock music facts, often enhanced by features about those facts. He has interviewed three of the four Beatles, all of Abba and been nursed through a bad attack of food poisoning on a tour bus in South America by Robert Smith of The Cure.