"Yorkshire lads shouldn’t marry American actresses": How MTV and David Coverdale's wife made Whitesnake into megastars

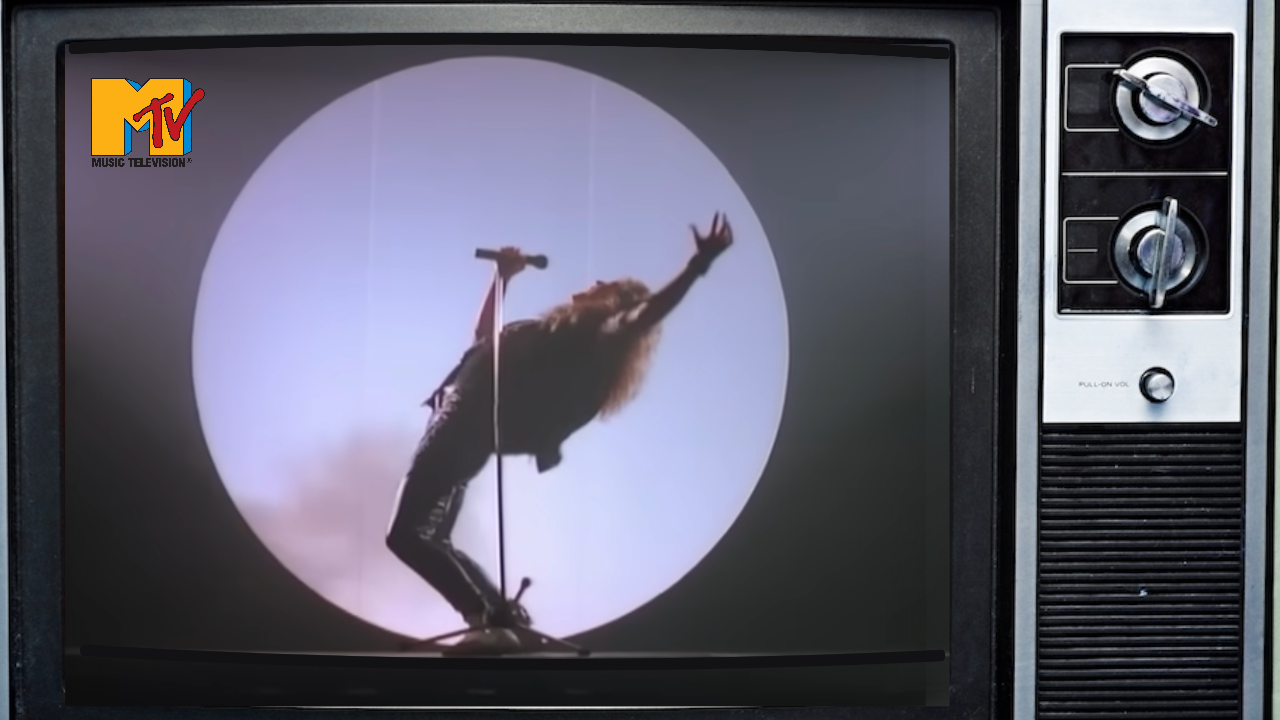

As MTV announces it will no longer play music videos in the UK and Europe, we look back at the moment it helped reinvent Whitesnake

“Oooh, hello, cheeky.” David Coverdale breaks off from our interview to greet a vision emerging from one of the many fabulous bedrooms found in what was then London’s most expensive hotel room – the penthouse suite at the Ritz Carlton in Kensington, at £1,200 a night.

The night before, the suite had hosted King Hussein of Jordan. Today, it was the no less regal Coverdale, with his Roman nose and rows of glistening teeth; the white T-shirt and the fancy waistcoat; the black riding boots; the jodhpurs; that fabulous meringue on his head. And here he was, introducing us to a woman, familiar in the same way that he was: from video, from television, from MTV.

“Jon," he says, "I’d like you to meet the wife. She’s been lying down. She’s been lying down because she’s been shopping.”

The last time I had seen “the wife”, she’d been doing cartwheels over a car bonnet in a rightly famous Whitesnake video.

This was Tawny Kitaen, lately the star of The Perils Of Gwendoline In The Land Of Yik Yak (1984) and the equally influential Witchboard (1986). Not necessarily a CV that qualified her for the job of being chased down an alley by David for the Still Of The Night video clip, but she'd beaten the pre-fame Claudia Schiffer, who had been promised the role.

“Hello,” she said, and smiled that smile – the smile that had David smiling all the way to the bank. We all smiled back. It was great.

When Tawny met David, her real name was Julie Kitaen, and she’d been around the LA metal scene for a while. She was born in San Diego in 1961, and by ’84 she was in B-movies and had a walk-on part in an early Tom Hanks picture, Bachelor Party.

David and Tawny had married in 1989 after a passionate courtship. David called her “my whore and my inspiration”. And although Whitesnake’s career-making album, 1987, had been in the can for two years, its real story was the story of David and Tawny, a serendipitous union of image and substance that completed a dramatic reinvention for both Coverdale and Whitesnake alike.

There are many great anecdotes about David Coverdale. My favourite was from photographer Ross Halfin, who had visited the Coverdale acreage at Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Camped around the pool and surrounded by nothing but sun, lake and endless desert, Halfin heard the unmistakable chirpings of English songbirds. This continued for some while, despite the lack of anything feathered in the vicinity.

Naturally puzzled, Halfin enquired of his host: “David, do you have an aviary?” Waving a slightly shameful hand, Coverdale paused and then admitted: “It’s a tape, dear boy… a tape.”

Even his speaking voice had become a curious amalgam of his North-East roots and the landed gentry, charming to the Americans but an anomaly to us Brits. But we forgave him because he was a charismatic man and a great rock star. It was also unfair to expect him to be normal, because his life had been so extraordinary.

He had gone from the obscurity of a sales job in a boutique in Redcar to replacing Ian Gillan in Deep Purple. No clubs, no steady adjustment, just one day a shirt salesman, the next, frontman for a band who were already hugely famous and influential.

When Deep Purple split up, its component parts found themselves unable to replicate such success. From the distant, untouchably remote Purple, here came Gillan and Rainbow and Whitesnake to a civic hall near you.

None filled stadiums with their solid, unspectacular rock. None hinted at anything more than competence sustained by fleeting inspiration. And all existed in an incestuous circle, with members joining and quitting each other’s bands while hankering for something bigger. The David Coverdale who had performed in the enormodomes of Japan and America was wearing a snakeskin tie and growing a gut.

By his side were men who defined the term ‘muso’: clubbing bluesers like Bernie Marsden and Micky Moody; men in the tradition of the skilled, jobbing player unused to the separation that stardom put between band and audience. Whitesnake made good albums, and they occasionally wrote great songs: Ain’t Gonna Cry No More, Fool For Your Loving. They produced a killer record, but it was spread thinly over five or six releases.

Fortunately for Coverdale, David Geffen and John Kalodner were curiously driven men. Headhunted for Geffen’s new label, Kalodner had taken Cher from Vegas cabaret feather shows to soft-rock queen. He also adopted Aerosmith and coaxed them to better their past artistically and commercially. Geffen telephoned Coverdale in 1984.

“Until David Geffen called me, I didn’t really work America as Whitesnake, I worked the rest of the world,” Coverdale recalled. “In fact in ’84 I had broken all attendance and merchandise records in Europe, but I still lost three grand! My first marriage was in tatters and then David Geffen called up and said: ‘It is about time that you took America seriously.’ There was nothing to keep me in London. So rather than taking pot shots at America from across the pond, I decided to relocate. And I had an extraordinary five years.”

Geffen were interested in Coverdale, not Whitesnake. He had the voice and the temperament, they knew that much. With a tan and some blond highlights he looked fabulous, too. But he needed a band. He needed to be surrounded by the sort of people who were making it in LA.

This was the time of Bon Jovi’s breakthrough. They were young and good looking. They were loud, brash and hairy. It was easy to see how a man of pedigree might fit in and also stand out. But he needed what in marketing circles is called ‘furniture’. The old bluesers, however integral to Whitesnake’s European sound, were more like sprung and busted old sofas. Bernie Marsden had to go. So did Micky Moody and Cozy Powell and the rest of the band.

John Sykes, on the other hand, was the real deal. As a writing partner, he was a provider of the sort of vast, suggestive guitar riffs that complemented Coverdale’s voice. As a star, he also fitted the bill: chiselled, tanned and undeniably hairy. As Coverdale indulged his Led Zeppelin fetishes in the studio with Sykes, the steady rhythm section of bassist Neil Murray and the veteran drummer Ainsley Dunbar provided the necessary anchor. But come the time for image, come the real reinvention, they would never do. Dunbar was made for drumming, not for TV, and most certainly not for MTV.

For MTV you needed lookers who could play. Coverdale needed a partner for Sykes in the pretty Adrian Vandenberg, he needed the lush hair of Rudy Sarzo, and he could even get away with the lived-in ruggedness of Tommy Aldridge tucked behind the kit. With the sound and the look, Geffen, Kalodner and Coverdale had hit on something. It was loud and powerful, suggestive of the classic vibes of Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple (Crying In The Rain and Still Of The Night), but it was also soulful and chart-friendly (Is This Love and the dusted-off Here I Go Again).

It was an album for its time, packaged and produced and just-so, but also organic and meaningful. It even took its title from the year of release, so well did it capture the zeitgeist. After a 15-year hiatus, David Coverdale was once again in the right place at the right time.

In an infamous interview with Sounds, he was asked if the video for Still Of The Night was not slightly suggestive of a rape fantasy, what with Tawny Kitaen walking at night past a dimly-lit chain-link fence, with Coverdale in pursuit, all the while taking uneasy glances back at him.

“You’d probably see it differently after a few beers,” he told the (male) journalist, and thus defined the image-governed unreality of the times. He was engaged in a love affair with Tawny, and with America. They were a golden couple. Both fulfilled a need for the other. Tawny wanted to be a star, and David was her platform. She was on television countless times a day. And when Whitesnake songs played on the radio stations, the listeners sat back in their cars and thought of her. By the time we met in Kensington, they were as well-known as daytime soap stars.

In a year and a half, 1987 sold eight million copies, propelled by the three videos that starred Tawny. A video compilation of the clips, Trilogy, sold over a million units, too.

By the time David had sacked half of the band, hired guitarist Steve Vai, lost direction and sold more records than Deep Purple had ever managed to do, it was all over. His marriage, the glory days of heavy metal, MTV’s Headbangers’ Ball, the era of the rock star as rock god, it was gone.

As with many grand passions, the lows were as low as the highs were high. Asked about his marriage, Coverdale responded: “I woke up from the nightmare… a few million dollars later. Yorkshire lads shouldn’t marry American actresses.”

Grunge had arrived. Heavy rock of the kind practised so well by Coverdale had become anachronistic, symbolic of the excesses that the new rock forcefully rejected. And the sun of LA gave way to the rain and reality of Seattle.

Even Tawny didn’t want to be Tawny any more, it seemed. She got a job hosting a TV show, America’s Funniest People, and had a small role in Seinfeld. She met and married baseball pitcher Chuck Finley, and switched to using her given name, Julie.

She ran into trouble with the law and appeared on reality TV. Nothing she did recharged her profile to the level of her MTV heyday. And on May 7, 2021, Kitaen died at her Newport Beach home. She was just 59.

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock Present 1980s, in 2006.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Jon Hotten is an English author and journalist. He is best known for the books Muscle: A Writer's Trip Through a Sport with No Boundaries and The Years of the Locust. In June 2015 he published a novel, My Life And The Beautiful Music (Cape), based on his time in LA in the late 80s reporting on the heavy metal scene. He was a contributor to Kerrang! magazine from 1987–92 and currently contributes to Classic Rock. Hotten is the author of the popular cricket blog, The Old Batsman, and since February 2013 is a frequent contributor to The Cordon cricket blog at Cricinfo. His most recent book, Bat, Ball & Field, was published in 2022.