World Of Leather

Heavy metal pioneers? Tongue-in-cheek survivors? High-camp motorcycle enthusiasts? As Judas Priest gear up for their 17th album, it turns out the truth is funnier, stranger and darker…

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Last year, after Rob Halford had surgery on his back, he made a joke about it. At the age of 61, the Judas Priest singer admitted that the years were catching up with him. “The wonderful thing about heavy metal music is that it’s immortal,” he said. “But the creators are not bestowed with that attribute.”

What Halford didn’t say – in public, at least – was how serious that operation really was. That wry turn of phrase was typical of the man. “It’s that British thing,” he says now. “Keep calm and… keep playing the metal.” Another joke. The truth of the matter is that the medical procedure undergone by Halford carried with it an enormous risk.

Seated in an office at the London headquarters of Sony Music, where he and other members of Judas Priest are being interviewed for the release of the band’s new album Redeemer Of Souls, Halford says he had to have that operation. “I had a ruptured herniated disc that was pressing against my sciatic nerve,” he says. “I couldn’t walk. I was in agony, absolutely screaming with the pain.”

In a preliminary meeting with his neurosurgeon at a Birmingham hospital, he had been informed of what the procedure would entail. “They cut you open at the back and they shave your spine down and chip away at it,” Halford explains.

But on the day of the operation, just minutes before it was scheduled to start, he was warned of the potential complications. “The surgeon told me the operation was quite dangerous,” he says. “I was in so much excruciating pain that I said, ‘Just fucking do it, man! This is killing me!’ But he said, ‘I have to tell you this. You may be paralysed from the waist down.’ I go, ‘Okay…’ ‘You may be incontinent.’ I thought, ‘Well, I’m almost incontinent anyway, so don’t worry about that!’ ‘You may not wake up from the operation – because I’ll be working on your cortex to your brain.’ He’s telling me all this stuff as I was about to be put under, and I genuinely wasn’t thinking about the consequences, because I thought, ‘Anything’s better than this pain.’”

It was only after the operation was successfully completed that Halford realised how lucky he had been – when he gained a true measure of his own mortality that went beyond making a joke of it. “I’m very fortunate,” he says quietly. “I know that.”

Halford has spent the past 12 months in recovery. For a period, he was confined to a wheelchair. And there’s more surgery to come, for a separate condition: an umbilical hernia, resulting from muscle weakness in his abdominal area. The swelling caused by the hernia is clearly visible beneath Halford’s black shirt as he leans back on a sofa. He describes it, rather too graphically, as “like the Alien bursting forth”. There is, however, some good news. The surgery required will be simpler, with minimal risk of complications. “I got the back end sorted,” he says brightly. “Now I’ve got to the front end sorted. But you get old, and these things happen.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What this means for the short-term future of Judas Priest is nothing more than the inconvenience of scheduling their next tour around their singer’s medical itinerary. “My doctor will recommend whether I should have the op now or after the tour,” Halford says. But the bigger picture – of the band’s long-term future – is less clear. In the past four years, Judas Priest’s lengthy career has been in a process of winding down. And throughout these years, the band have sent out mixed messages. In 2010 it was announced that Priest’s world tour – significantly named Epitaph – would be their farewell. Halford subsequently issued a partial retraction, stating that Priest would continue to tour, albeit only on a limited basis.

This was followed on April 20, 2011 with the shock news that guitarist Kenneth ‘KK’ Downing, a founder member of the group, was retiring with immediate effect. In Downing’s absence, a new guitarist, Richie Faulkner, joined the band for the Epitaph tour, and has continued in that role on the new Priest album.

But it’s still undecided as to whether this album will be their last. In 2011, during the early stages of writing, guitarist Glenn Tipton contradicted himself when he said: “In a way, I suppose, it’s our farewell album, although it might not be our last one.” It was a mixed message in itself. And even now, Tipton is uncertain about where Judas Priest go from here. “I can’t really answer that question,” he says. “At the moment we’re energised. We’ve done what we feel is one of our best albums. But without being morbid or anything, you never know what’s around the corner.”

It was Black Sabbath that defined heavy metal music at the turn of the 70s, and Judas Priest that redefined it in the years that followed. A series of landmark albums – most notably Sad Wings Of Destiny from 1976, and British Steel from 1980 – established a signature sound based on the twin lead guitars of Tipton and Downing, and the high-register voice of Halford. Priest’s music would have a profound influence on bands such as Iron Maiden, Metallica, Queensrÿche and Slayer. And equally influential was Priest’s image, with Halford the exemplar in S&M-inspired black leather, studs and chains.

At the height of the band’s popularity in the early 80s, Priest were arguably the biggest metal band in the world. In 1983 they performed to 350,000 people at the US Festival in California, and two years later they appeared on the stage of Live Aid in Philadelphia to an estimated global TV audience of 1.9 billion. “Live Aid,” Tipton recalls, “was a day I shall never forget.”

There have been bad times as well as good. In the first half of the 80s, Halford was, by his own admission, hopelessly addicted to alcohol and drugs. In those less enlightened times, he was also hiding his homosexuality from the public for fear of alienating the band’s audience. “I put Priest before my own personal peace and tranquility,” he explains, “but I don’t think I had any choice.”

Worst of all, Halford says, was the lawsuit filed against the band in 1990 by the families of two young men who had committed suicide five years earlier: the principal allegation being that the men, James Vance and Raymond Belknap, had been driven to their suicide pact by a supposed subliminal message of “Do it!” hidden in the song Better By You, Better Than Me, from Priest’s 1978 album Stained Class. With Halford giving testimony as the band’s chief spokesman, the case was successfully defended.

Judas Priest survived this ordeal and continued even after Halford quit in 1992. He was out of the band for 11 years, pursuing more modern forms of metal and industrial music with Fight, 2wo and the eponymous Halford. In those years, Priest worked with a previously unknown singer, Ohio-born Tim Owens, who was plucked straight out of a Priest tribute band named British Steel – an unlikely story that formed the basis of the 2001 movie Rock Star, featuring Mark Wahlberg.

But in all the time that Halford was out of Priest, he never matched the success or the brilliance of what he achieved with them. Likewise, Priest suffered without him. The two albums they made with Owens made little impact. The young singer – nicknamed ‘Ripper’ after the Priest song – had plenty of gusto, but he was no Rob Halford. It was a long time coming, but Priest and Halford was a reunion waiting to happen.

In the history of Judas Priest, the dominant figures are Halford, Tipton and Downing. For the greater part of the band’s career, these three wrote the songs and defined the band.

Downing’s retirement leaves bassist Ian Hill as the sole remaining founder member in the group. Hill was 17 when the band formed in West Bromwich in 1970, and he has been a solid presence ever since. “I’m a laid-back sort of bloke,” he says. “It’s all I ever wanted to do – play bass in this band.” An amiable man, Hill laughs off the suggestion that he is, in the words of Spinal Tap’s Derek Smalls, the “lukewarm water” to the fire and ice of Halford and the guitarists.

What Downing’s exit also leaves is Halford and Tipton as the two leaders of the band. American drummer Scott Travis has served in Priest for 25 years, but is not put forward for interviews by management. And when the new boy, Richie Faulkner, is interviewed, there’s a palpable sense that he knows his place. He’s forthright in some of his opinions about the band, but he remains always deferential to Halford and Tipton.

Certainly, Glenn Tipton has exerted a powerful influence within Judas Priest across the years. Although he joined the band comparatively late – in 1974, one year after Halford joined, and five years after Downing and Hill put the original line-up together with singer Al Atkins and drummer John Ellis – Tipton quickly emerged as the senior songwriter in Priest, always credited first, ahead of Halford and Downing. And it was Tipton’s name, not Downing’s, on several songs that shaped the band’s career: The Ripper, Sinner, Exciter, Hell Bent For Leather. But when Tipton describes Judas Priest as “larger than life”, he is to a large extent describing Rob Halford – the totemic frontman with a huge persona and a one-in-a-million voice, the self-proclaimed Metal God.

Tipton and Halford are very different characters. When Tipton speaks to Classic Rock – from his home in Worcestershire, where the new Priest album was recorded – his voice carries a quiet authority, hardened by a somewhat dour manner. By contrast, Halford is open and engaging, thoughtful on the serious subjects, witty and self-deprecating when it comes to the sillier stuff. His only concession to rock-star posturing is the wearing of aviator shades during his interview, despite the low lighting in the room.

Another key difference between the two is in their lifestyles. Tipton devotes his time to his family when not working. Halford, meanwhile, is on-message all of the time. He retains a home in the Midlands, a modest place in Walsall that he’s owned since the 70s. “The first house I ever bought,” he says, “for twenty grand.” But his main residence is in Phoenix, Arizona, where he regularly attends gigs and rock clubs. “In America, it’s a much faster pace of life,” he says. “And that invigorates me – a bloke of my years. I like hanging out with bands.”

He’s also continually devouring information about new metal bands online. “I’m on a dozen metal sites a day,” he says. “I know what’s out there and I know where our place is. The older you get, the more cynical you tend to become, but I’m sixty-two and I’m not a cynic. I have to listen to metal every fucking day. I can’t do without it – it’s like water to me. I know everything about metal.” He adds, as if emphasis were needed: “I live it.”

Rob Halford might not have ended up as the singer in Judas Priest were it not for his sister Sue. In the early 70s, she was dating Ian Hill. The couple later married. But they were together for a year before she told him that her brother was a singer – and only then because Priest needed a new frontman after Al Atkins had quit.

The band owed its name to Atkins. In the late 60s, he had led an entirely different group, named Judas Priest after the Bob Dylan song The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest. When that band broke up, and Atkins hooked up with Downing and Hill, they kept the name. But in 1973, when Atkins’ wife fell pregnant, he left the band to work a regular job. At this time, the band had yet to release a record or make any serious money.

“There’s a watershed moment in everyone’s life,” Hill says. “You have to decide whether you’re going to take the happy mediocre route or go for the more dangerous one, where there might be fame and fortune at the end.”

When Halford joined the band, Hill and Downing gave up their day jobs: the former was a van driver, the latter an electrician. Within a year, Priest signed to Gull Records, a small-time label. And with Tipton added to the line-up, they recorded their debut album Rocka Rolla, released in 1974. “It was a very proud moment,” Hill recalls today, “walking into your local record store – Turner’s, in Paradise Street, West Bromwich – and your album’s on the shelf next to The Beatles and the Stones.”

It was with _Sad Wings Of Destiny_, their second album for Gull Records, that Priest truly defined their sound on the classic tracks Victim Of Changes and The Ripper. The album was strong enough to secure the band a deal with CBS: a dream come true, Hill says, to be on the same label as Bob Dylan. And with successive albums in the latter half of the decade – Sin After Sin, Stained Class, Killing Machine and the live recording Unleashed In The East – Priest became a major act. Following superstar bands such as Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple, Priest were in the second wave of heavy rock, rising alongside Thin Lizzy, AC/DC, Scorpions and UFO.

What elevated Priest to even greater stardom was the 1980 album British Steel, which yielded two Top 20 UK hits in Breaking The Law and Living After Midnight. That album also established Priest in America – a breakthrough consolidated by 1983’s Screaming For Vengeance, which sold two million copies in the US. And in that heady era, the band succumbed to the excesses of the rock’n’roll lifestyle – Halford most of all.

“I was a fucking raving alcoholic drug addict,” he says. “Cocaine was my drug of choice. I’d drink Jack Daniel’s, Dom Perignon and sixteen-ounce cans of Budweiser. And I’d have vodka and tonic through the show. I was off my trolley, but thank the Lord I didn’t become a casualty. I stopped on January 6, 1986, and I haven’t had a drink or a drug since. I wouldn’t want to. I never want to feel that way again – feeling crap all the time, when the only way I could stop feeling crap was to put more crap in me.”

During Priest’s wild years, Halford never spoke to journalists about his drinking and drug taking. For him it was not a badge of honour as it was for Ozzy Osbourne or Mötley Crüe. He also never spoke openly of his sexuality.

In 1986, two American filmmakers, Jeff Krulik and John Heyn, made a documentary about the culture of heavy metal. At a Priest concert at the Capital Center in Landover, Maryland, they filmed fans congregating outside the venue ahead of the show. Typically, these fans were young white males. Most were apparently drunk, stoned or both. The resulting 20-minute film was entitled Heavy Metal Parking Lot, and its defining moment came when a slurring brunette is asked what she would do if she met Rob Halford. Her reply: “I’d jump his bones.”

“It was so funny when she said that,” Halford says now. “I thought, ‘She doesn’t realise the kind of bones I like to jump!’”

Halford’s sexuality had for many years been an open secret within the music business. His image was not unlike the biker in The Village People: he was a gay man hidden in plain sight. And he kept his counsel because he feared that in those less enlightened times, Priest’s audience might have deserted the band.

“That’s why I didn’t reveal myself,” he says. “Much like Freddie Mercury would never say, ‘I’m gay.’ Freddie was like, ‘That’s my private life. I don’t talk about that.’ But everybody knew that Freddie might be – you know – one of the boys. I was particularly careful not to be caught in a gay bar or to be seen with a boyfriend. That’s what gay guys do, even now. When I look back, it would have been a very dangerous thing to do. The mental landscape wasn’t prepared.”

Halford revealed his sexuality to the other members of Judas Priest in the mid-70s. “Rob decided not to announce it to the world, which then was probably the correct decision,” Hill says. “Back then it was a different time. His mum and dad were also alive, and they’re from a different era completely, so maybe that was weighing on his mind. If Rob had wanted to announce it, I don’t think any of us would have said, ‘No, don’t do it.’ We’d have backed him to the hilt. Rob wasn’t just a colleague – he was a close personal friend. But when he did finally come out, it was no big deal.”

It was in 1998 that Halford eventually broke the news in an interview for MTV. The reaction from the public – and from Priest fans especially – was overwhelmingly supportive. But as he says now: “We’ve still got a long way to go. Some of us are still killed for being gay. A couple of years ago, in Iran, two teenage lovers were hung in public, side by side. I just fucking lost it that day. I know what it feels like to be in a minority and not to be accepted and not being given equality. I’m not a spokesperson. If I go and stand on a stage in St. Petersburg in Russia and start talking about gay stuff, I’m going to be arrested. I’m not going to do that because I don’t want to ruin a night for the fans. But just by me standing there, I’m making that statement. Just being who I am, standing on that stage in a country that hates people like me, it’s a victory. There are readers of your magazine that are probably struggling with their identity, and I urge anybody: don’t give a fuck. It’s your life. Don’t live it for anybody else – like I did in the eighties.”

He pauses for a moment and then smiles. “The strange thing,” he says, “is that I still get women wanting to do me. And in the past I have experimented with females. It’s not all cock and bollocks, you know. Even now, although I’m a gay guy, I know a beautiful woman when I see one. And I think that’s why I have so many female fans – they want to turn me!”

Glenn Tipton never considered splitting the band when Halford left. “We were determined to carry on,” he says. “We couldn’t just give up.” It was only after KK Downing quit in 2011 that Tipton seriously doubted whether Priest had a future. “At that point,” he says, “we really did think it was over.”

At this late stage of the band’s career, finding a new guitarist wasn’t going to be easy. “We were in a pretty dangerous place when Ken retired,” Halford says. “We didn’t know what was going to happen. Ken will always live in Judas Priest. He’s a legend. But things happen in life, much like when I went off. You just have to accept it.”

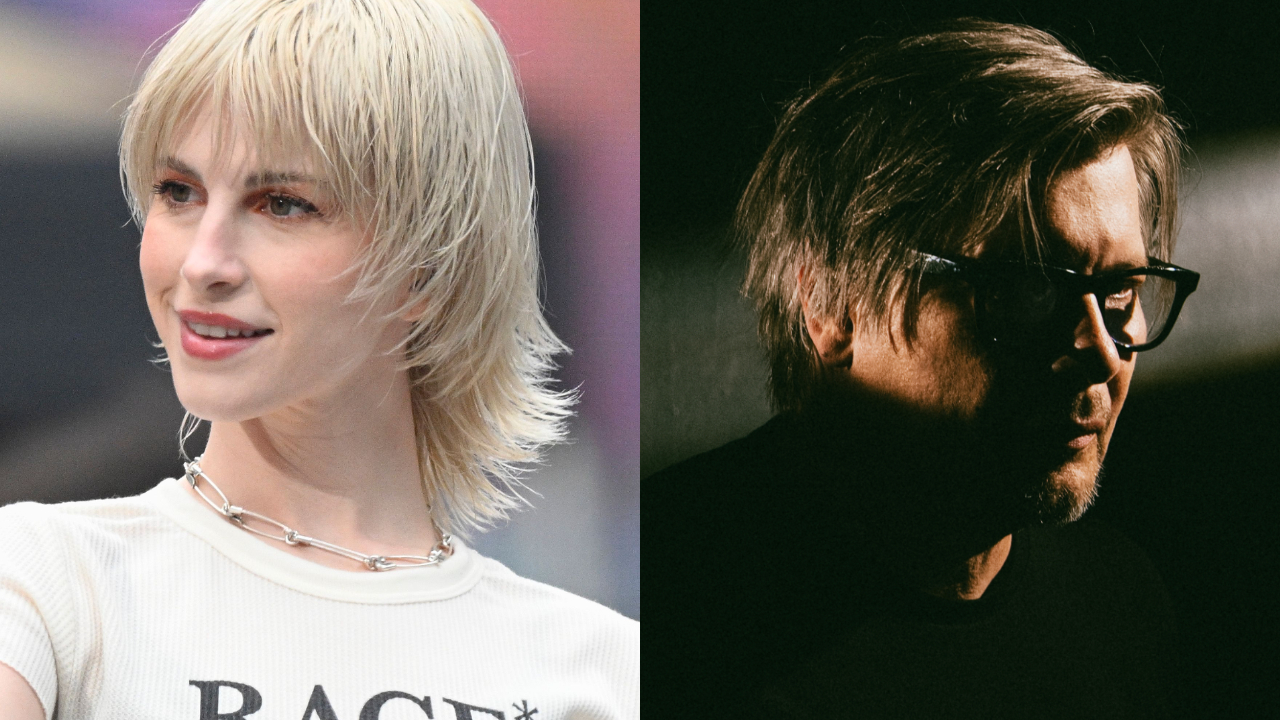

When Richie Faulkner auditioned for Priest, he was at a crossroads in his life. At 31, the Londoner had been a jobbing musician for 10 years, and the closest he’d come to any real success was in a backing band for Lauren Harris, the daughter of Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris. Faulkner was thinking about jacking it in. “The music business is so fickle,” he says. “I was tired of the unpredictability, living paycheck to paycheck. So I was looking into other careers, like fireman, airline pilot…”

For Faulkner, joining Judas Priest wasn’t just a job. Like Tim Owens before him, he’s a fan of the band, and feels like he’s won the lottery. “I was raised on classic Priest,” he says. “As a kid, I practised those moves with a cricket bat in front of the mirror. I’m incredibly fortunate. This is what I aspired to. These guys created the dream for me.”

Tipton, a man not easily given to hyperbole, says it was “a small miracle” they found Faulkner. “Without Richie,” he says, “I don’t think Priest would be here now.”

With Faulkner embraced by Tipton and Halford as part of the writing team, the new Priest album Redeemer Of Souls is the third they’ve made since Halford’s return in 2003. And if not a classic Priest album, it’s certainly in the classic Priest tradition. March Of The Damned, the first new track premiered on the band’s website, is misleading. Halford thinks it’s reminiscent of the “stripped down” style of British Steel. In reality, it sounds like an Ozzy Osbourne outtake. There’s much better material on the album. The opening track Dragonaut is much more evocative of British Steel. Beginning Of The End, an elegant ballad, has echoes of their existentialist masterpiece Beyond The Realms Of Death. And on Crossfire, they go back to their roots in the British blues-rock era – a throwback to their version of Peter Green’s mystical Fleetwood Mac song The Green Manalishi (With The Two-Prong Crown).

“There’s nothing contrived about this album,” Tipton says. “It just came out naturally. And I think it’s what most Priest fans would want us to do. Priest music is pretty timeless.”

Halford says the direct style of the new album is in part a reaction to what came before it. Their 2008 concept album Nostradamus, based on the life of the French seer, had overblown orchestral themes that left many fans bemused. “Nostradamus was a very thought-out, methodically planned record,” he says. “This one is really straight from the heart – the classic essence of Priest.”

He also concedes that there is one track on the album that borders on self-parody. Its title: Metalizer. Halford has been here before. On the 1989 album Ram It Down was the track Heavy Metal, with a chorus in which he stated rhetorically: ‘Heavy metal. What do you want? Heavy metal.’ Halford recalls it with a knowing laugh. “Simple, isn’t it? Like, ‘She loves you, yeah yeah yeah.’ But I think you know internally whether you’re stepping into something that’s almost satirical. If you’re intelligent enough, you will really understand and appreciate what you’ve created and you’ll embrace it, without blowing it up into a cartoon.

“Metalizer, Heavy Metal… why not? That’s who we are, that’s what we do. We’re one of two bands that invented heavy metal, Black Sabbath and Judas Priest. Sabbath have just had one of the biggest albums of their career with 13. It’s unashamedly Black Sabbath. And I’d like to feel that Redeemer Of Souls is unashamedly Judas Priest. I think we were looking to see if we’d still got it in us – and thankfully we do.”

Whether Judas Priest have it in them for the longer haul, Halford and Tipton cannot say. When Halford thinks back to the crazy days of the 70s and 80s, he wonders how they ever got through it all. “Back then we made a record every year and we’d tour the world. We did four or five records and tours like that, back to back. How did we do that? My mind just can’t relate.”

The future for Judas Priest is undecided. The only certainty is that for this legendary band, these are now the end times. “We’ll just have to see how it goes,” Tipton says. “I think that’s all we can do. But we enjoy this band so much. It’s a very difficult thing to give up.”

“We treasure this band,” Halford adds, “and what we’ve created are treasured memories for a lot of people. That’s the extraordinary place we find ourselves in. I’m in a band called Judas Priest, and I think quite deeply and affectionately about that. It’s magical.”

Redeemer Of Souls is out now via Sony.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”