Greg Puciato: “it felt really good when Dillinger split”

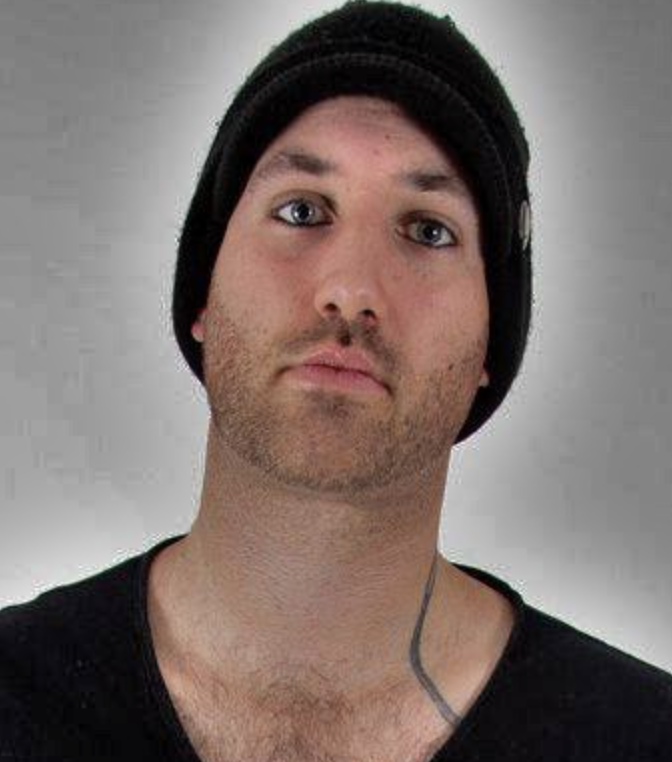

From The Dillinger Escape Plan‘s chaotic beginnings to the “trauma” of their ending , Greg Puciato looks back over life on heavy music’s frontline

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 2001, Greg Puciato became the frontman of notoriously chaotic upstarts The Dillinger Escape Plan. Not only did Dillinger’s live shows become legendary for the way that Greg and his bandmates pushed their bodies to the limit, the records they made showed incredible growth; from the mathnoise terrorism of their early days to the vast, alt-synth-jazzmetal mash-ups of their latter albums, none of it would have been possible without Greg’s pipes.

As we introduce ourselves over Zoom, and joke that every question will be about his infamous bowel movement onstage at Reading Festival in 2002, he sighs and tells us, “It’s so weird, because it never gets brought up anywhere else except the UK! I’d just say the same thing I have already said.”

His boredom with the topic is fair enough, because there’s so much more to the man than one dirty protest from 20 years ago. Metal mourned when Dillinger called it quits in 2017, but it was far from the end for Greg. He’s continued to explore his creative urges in supergroup Killer Be Killed (alongside legends Max Cavalera and Troy Sanders), released ambient electro-pop albums with his band The Black Queen, and produced impossible-to-categorise solo material, including his new album, Mirrorcell.

He also worked on Brighten, last year’s solo album from Alice In Chains guitarist Jerry Cantrell, who calls during our conversation. Greg, ever the gentleman, will ignore it and tell us, “You’re more important.”

Aww, shucks! It’s clear Greg’s the most fascinating character on this particular call, as he talks us through his life story.

What’s your first memory associated with music?

“It’s so long ago that I don’t really remember, but I do have this weird recollection of having this fake record player that played one song – it was a Smurfs song or something. I might have been about three years old. I have this memory that I knew it was coming out of this thing, and I wanted to play it over and over again.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It’s really difficult to remember anything that was real music… my Dad was really into REO Speedwagon, and my parents took me to see them when I was about four or five, and I remember that, because my mother had put cotton balls in my ears and I didn’t like the way it sounded, so I took them out, and to this day I’ve never worn earplugs. After that it’s a fast-track through to Metallica and all that.”

When was the first time you did something creative?

“I was insanely creative at a young age. My mother told me I had a toy drum set that I wouldn’t stop playing, but by the time I was in kindergarten I was trying to write stories; I had a little composition book of characters who’d get superpowers when they ate M&Ms. I used to write them every day, then one day… I just didn’t. But it was like a distraction. I couldn’t do any work at school, I was so not present; they would ask me to do something and I just couldn’t, because I had all these stories going through my mind.”

This would have been a long time before your diagnosis of ADD, right?

“Yeah. It just didn’t really exist then. It was something that no one really knew about. It wasn’t until high school that I even heard the term. If you’re going down the route of, ‘Is ADD related to creativity?’ I think it’s massive.”

How hard was it for you at school coping with that undiagnosed condition?

“People with ADD are often thought of as really smart, because their brains are fast, and teachers did get frustrated with me. They always had the same chat with my parents over and over again, about me not paying attention and doing things at the last minute. I can’t do shit that I don’t want to do, but I never thought of that as anything other than it was frustrating. I knew that I was different because I just couldn’t do shit and I knew other people could, even just getting up in the morning… I saw people were doing it, and I just couldn’t.

By the time I got to college and we were having to write these essays, fuck, I couldn’t even get through a chapter of a book. I might not have read an entire book for all of high school; I just skimmed it and bullshitted it. But I was really good at writing. I had a teacher tell me I was the best writer they’d seen in 30 years, but it was such a shame that I didn’t apply it. And I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’ll apply it in a different framework than the one you assume everyone should go down’, and that’s kinda what happened.”

You played guitar early on, didn’t you?

“Yeah, I knew a drummer and I’d take my amp over to his and we’d jam, like, Nirvana or whatever. But when I started to write my own stuff then that was it – I was obsessed, and that was all I could do. I used to take my amp over on a skateboard and refuse to leave my gear at his house in case I woke up at 3am and needed to write a riff.

It was exciting; it was that stage where you aren’t even a band, but this nameless thing means everything to you, that wide-eyed determinism of youth to believe you’re on the road to being the new Metallica. I actually have used some of the riffs that I wrote at that time for Killer Be Killed, and I felt kinda guilty about it out of loyalty to that project, but it was funny to say when Max [Cavalera] asked me where that riff came from that I wrote it when I was 13.”

You were a fan of The Dillinger Escape Plan before you joined, weren’t you?

“It’s funny, up until recently there were only two periods in my life: pre- and post-Dillinger. It was such a massive thing in my life but, if you’re talking about when I first joined, I had only been a fan for a little while, probably right before [1999 debut album] Calculating Infinity came out. They were unique and I could tell it was something worth paying attention to. I don’t think that people understand how jarring it was back then – that record was like a lightning bolt from another planet.

I went to see Candiria in Baltimore, and I remember standing outside talking to some kid I knew from the scene. I asked if he’d heard of The Dillinger Escape Plan and he said, ‘Yeah, shame they split up.’ And I was like, ‘What?’ and he told me they had lost their singer and he thought they were auditioning people but it probably wasn’t going to go anywhere.”

That’s when your ears pricked up!

“Yeah, he said I should go look on their website. This is the early days of the internet, with dial-up modems, and it takes 10 minutes to load all that shit. I didn’t even have internet access at that point; I had to go to my local library the next day. Sure enough, there’s an address to email a tape to and an instrumental of 43% Burnt. I thought I’d give it a crack. I hit up a friend in a local studio and decided to do two takes, one as if I’d never heard the song before and write all new lyrics, and then a mimic of what was already there. That was it. I only made one copy… I don’t know where it is now.

I didn’t hear anything and I decided to email the page again; they hit me straight back. Apparently, I didn’t leave any contact details. Ben [Weinman, Dillinger guitarist] said, ‘You’re basically the only person we want to audition. Can you come up tomorrow?’ I had this part-time job, and they wouldn’t give me the day off, so I quit the job. I learned the songs on the four-hour drive to New Jersey. I went up a couple of times and tried out.

The second time they said, ‘We’re not being rude but we need to talk privately’, and they left me in this room for, like, two hours. They came back and they had gone to eat at a diner and just left me there to fuck with me and see what I’d do. Then they nonchalantly said, ‘If you wanna do this, let’s do it.’ But it didn’t really feel like anything other than joining a local band.”

It grew so quickly after you joined. Did the System Of A Down tour in 2002 play a big part in that?

“We were part of this Relapse Records, grindcore scene – these bands like Coalesce, Botch. No one was really talking about it until the System thing happened. We were in the van in the United States; playing rooms to 200 people felt like a big show. If there were 70 people there, we didn’t see that as a bad show, our scale of size was there… we thought there was no way a band like ours was going to get any bigger than that.

Anyway, we had this friend of a friend who was our manager, and he said that Daron [Malakian, guitarist] from System Of A Down had been in touch about getting us to open on this European tour starting in two weeks. We were like, ‘WHAT?!’ We asked what size rooms, and they said it was all booked as arenas, and there was a soccer stadium in Italy – big, giant places and they’re already all sold out. It was for no money, but we knew we had to do it.

That tour changed everything for us. We never would have done Reading and Leeds, any of those big European shows, the press we got in the NME or whatever, it all came from being on that tour. When we came back, we were two or three times the size we were previously.”

But the reaction from SOAD fans was… let’s be polite and say you were polarising.

“Well, we had a defiance that came from pushing against everything. We held onto that right until the end. Even when we were doing 3,000 people in London or whatever, we still thought we were this upstart band. We still thought of ourselves as this young band saying ‘fuck you’ to everything. But on that tour, we were getting booed mercilessly; it did not seem successful at the time.

It was only when we came back and realised that if you are usually playing to 200 people, and you then get 800 of a 5,000-strong crowd into you… that’s a huge difference for our size. Suddenly there were 600 people where there used to be 200. We realised that something had happened.

But we were getting booed so badly that we couldn’t even hear our monitors, and that gave us this idea that everyone hated us, and we just used it as fuel. We hated the fans, the industry for holding us back, other bands for not being as good as us and not taking us on tour because they were scared of us. Everything became this thing to push against.”

How hard was it when you ended up in tabloid publications in 2012, due to your relationship with adult actress Jenna Haze?

“That was super-weird. At that point I lived in LA, I was around a lot of celebrity culture, but it was weird. I didn’t see it as being a big deal, and then it became blown out of proportion and made me sour on a lot of media outlets. It was another snowball of ‘fuck you!’ It really coloured the next 10 years of my life.

I began to shield myself a lot more, I got off social media, I became a lot more protective of my personal life. It was really uncomfortable for me and everyone in the band. It became something that became a theme, your personal life becoming a talking point, and I have no interest in celebrity at all. I didn’t think people would care, but they do. If you don’t wanna lose it completely you have to pull back."

Dillinger split in 2017. What were your initial emotions in the aftermath of that?

“It felt really good. It felt like we were going into a black hole, the preceding five years had got progressively worse. Personal developments that we weren’t making, because that’s what it was, were stunting our growth. You’re in this bubble on tour where your ability to live life is really skewed; you’re getting more and more isolated from normal life.

When we announced we were splitting up, those two years on tour were particularly bad. It shifted our momentum; you’re getting bigger but it’s not because of what you’re doing, it’s because they don’t want to miss you. It feels like you’ve been diagnosed with this illness and you’re dragging this dying thing around with you.

Everyone is coming to say goodbye to you. It was no longer fun at all, we were not getting along personally, every single show was the last show, like a funeral, at every single city. It gives you nothing. One or two shows like that is cool, 300 shows like that, it’s like a poison. It freed us all so much to grow; we became people we needed to be without the band.”

Plus, all the trauma that happened on that tour as well.

“Yeah, it never ended. From the time we announced we were splitting, it seemed to ramp up the bummer; we had the bus accident [in Poland in 2017], Chris Cornell killed himself while we were on tour with them. What the fuck?! At first, we thought touring with Soundgarden was proof that cool shit could still happen, we had a moment where we were inspired again.

Then Chris went mid-tour, I saw him the night before, even that is tied to that tour. The bus accident as well, it felt like the universe was telling us to stop, like this is not the energy that we should be bringing. It got to a metaphorical sprint to the finish line, ‘Get this shit over before we get in a plane crash.’ It spooked us a little bit.”

Your solo material is so wonderfully eclectic, it feels like a great reflection of your personality.

“Thank you, man. I just knew I needed an outlet for all of this shit. It was all need-based for me. I needed to create a home for this music I was making, and I didn’t think I’d put it out in my birth name, because our scene just doesn’t do that. I thought it would be audacious and ridiculous, but every other genre does that. As soon as I did it, it just really felt right.

It was weird coming from a band like Dillinger to do that, but I spoke to Jerry Cantrell and asked him what I should call it. He said, ‘Just call it your name.’ And I thought it was weird, and he went, ‘So, should I give Jerry Cantrell a band name?’ And no, of course not. It isn’t weird, and I should own being an adult artist, and it just became so fucking freeing.”

Mirrorcell is out now via Federal Prisoner

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.