Atari Teenage Riot: A Band Born From Chaos

Alec Empire talks German politics, internet activism and *that* Brixton show

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

On November 29, 1999, at the personal invitation of Trent Reznor, Atari Teenage Riot closed out their year-long Revolution Action world tour with a show supporting Nine Inch Nails at London’s Brixton Academy. In theory, the night should have been a glorious celebration, an end-of-the-century victory lap for the band, who’d emerged from the Berlin underground electro scene to become one of the most respected, forward-thinking acts of the decade. The reality was somewhat different.

ATR were burned out – exhausted, sick, sore and unravelling mentally and physically. One month earlier, ahead of the opening date of a UK headline tour, MC Carl Crack had suffered a psychotic episode and attempted to force open the exit door of a plane bound for Belfast while it taxied on the runaway, attacking a stewardess when she sought to restrain him: the authorities were now seeking to commit him to a mental asylum. Singer Hanin Elias had her own health issues, and had spent the previous week throwing up onstage and coughing up blood. Frontman Alec Empire was suffering too, relying on industrial-strength painkillers to make it through the shows. “Every day,” he recalls, “all we talked about was stopping.”

“We were all really fucked up,” says Empire, speaking to Hammer from his Berlin studio. “Because we were on tour there was never time to get proper medical treatment, and whenever I did see a doctor, the message was always the same – ‘You need to rest, you are destroying yourself’. I’d be like ‘Yeah, whatever.’ But something had to give.”

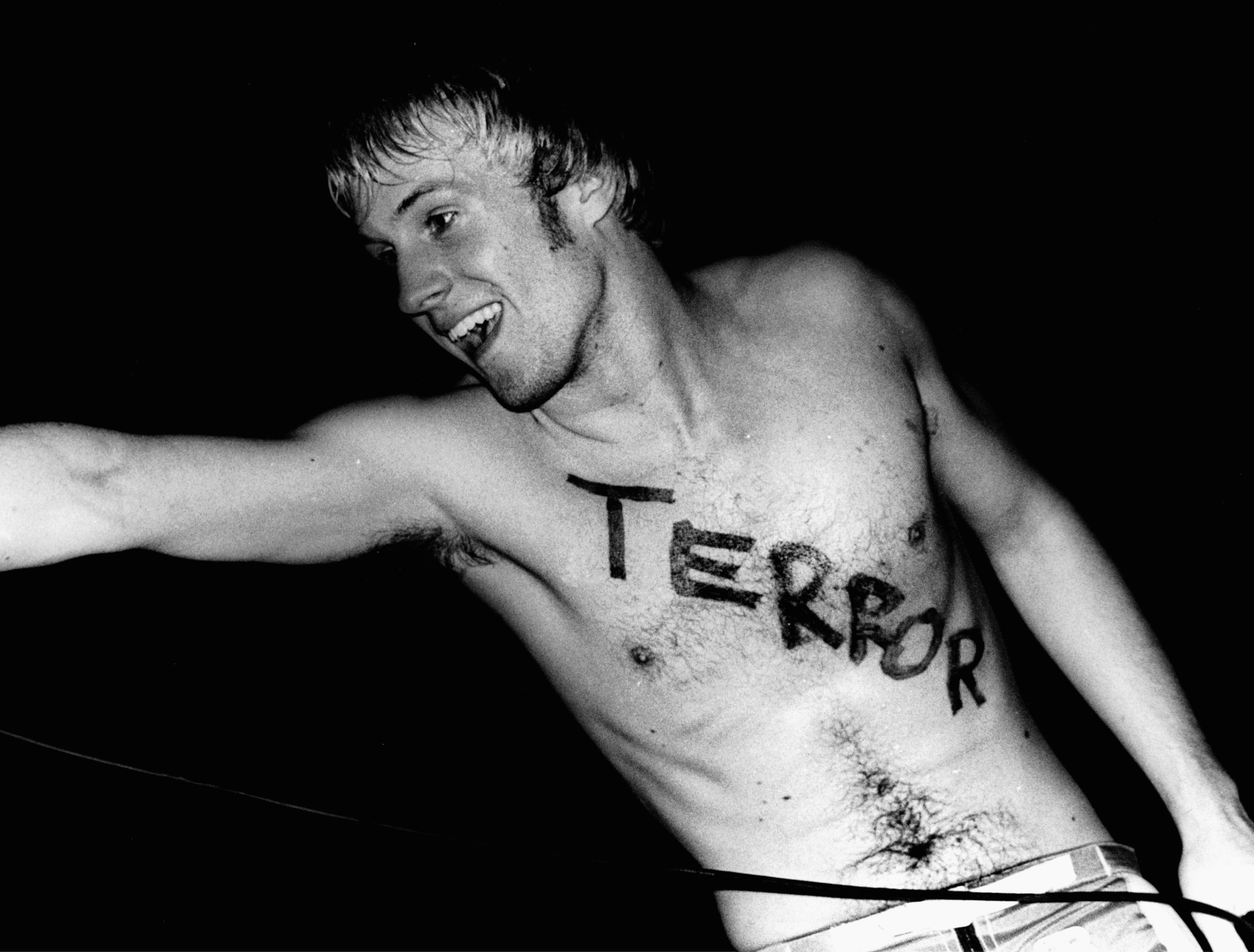

Backstage at Brixton Academy on that November night, when Elias decided she was too ill to perform, Empire, Endo and Crack convened an emergency band meeting. They decided to abandon any notion of playing actual ‘songs’, opting instead to collate all their harshest, most distorted, atonal samples into a barrage of pure noise – “proper riot music”, Empire recalls. Safe to say, Brixton had no idea what was coming. For the next 30 minutes, 5,000 industrial rock fans stood with their fingers in their ears and their jaws on the floor as the Berliners unleashed a cacophony of white noise, entirely without form or structure, at maximum volume. The mood in the room veered from bemusement to outright hostility, with pint glasses being hurled toward the stage and middle fingers being thrust into the band’s faces. This wasn’t entertainment, this was all-out war.

“It was really interesting,” laughs Empire. “To this day, people say that there hasn’t been a comparable pure noise show on that level. In his book The Electronic Revolution William Burroughs wrote about how you can create riot sounds and that, in turn, creates panic, because people don’t know what’s going on, and then a real riot can break out. I always thought that was such a great idea for a band, building that intensity of noise to push things into chaos. We definitely did that that night. And it was a lot of fun. But it was also a definite end point for that era of the band.”

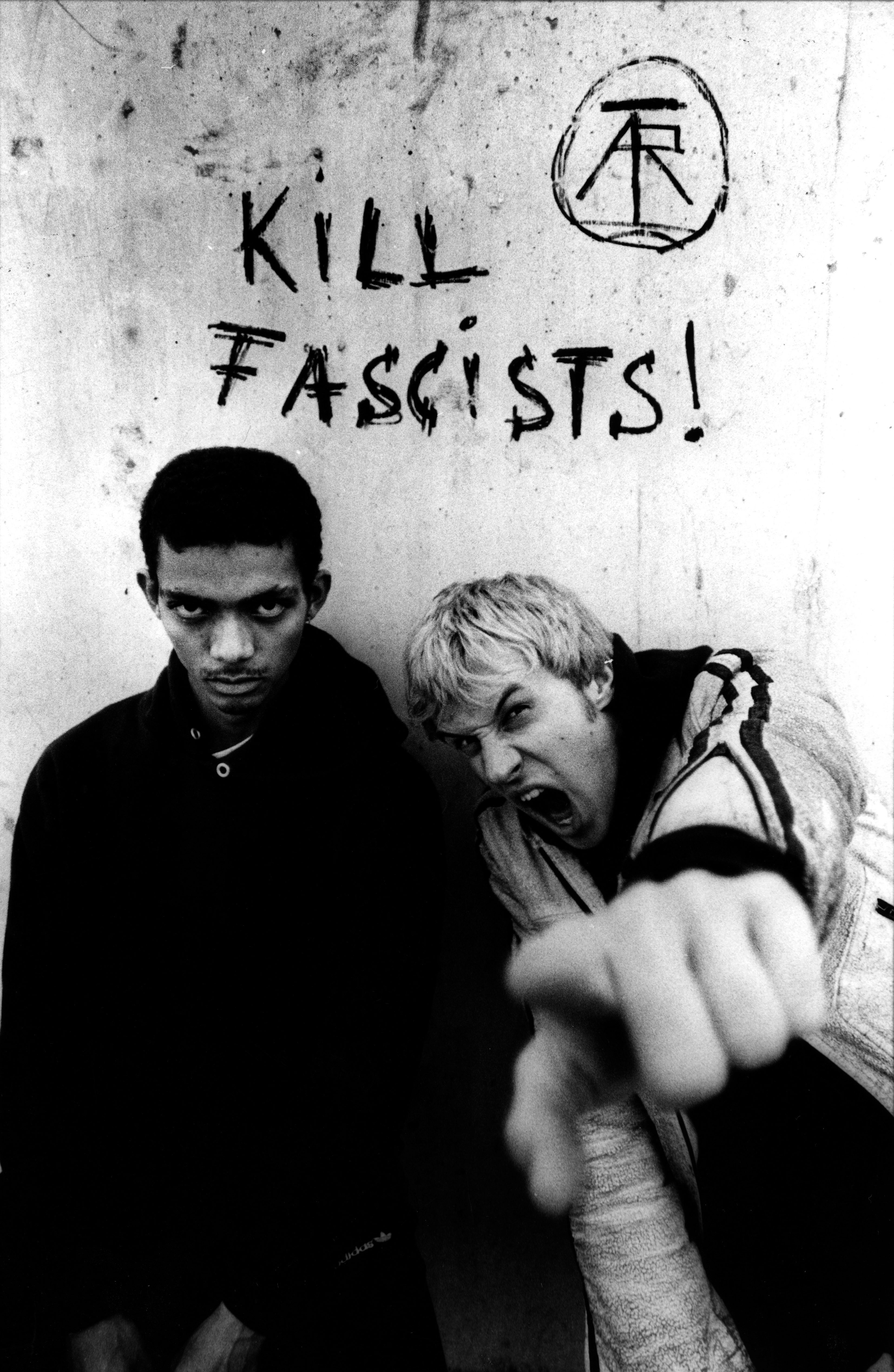

Atari Teenage Riot were a band born from chaos. Growing up in the shadow of the Berlin Wall as part of a proudly left-wing family, Alec Empire (aka Alexander Wilke-Steinhof) was always attracted to rebel sounds, forming his first punk band Die Kinder (‘The Kids’) at the age of twelve before immersing himself in the city’s nascent hip-hop and underground techno scenes. ATR came together in 1992, born of a shared mission to blend aggressive ‘digital hardcore’ sounds with fiercely uncompromising anti-fascist politics, in reaction to the resurgence of neo-Nazi movements in Germany. Early ATR gigs saw fans clash with far-right protestors who tried to disrupt their shows, which only served to strengthen the group’s desire to confront and challenge, manifested in tracks such as Start The Riot!, Deutschland (Has Gotta Die), the Sex Pistols-sampling Delete Yourself! and the self-explanatory Hetzjagd Auf Nazis! (’Hunt Down The Nazis!’)

“Since the fall of the Berlin Wall you could say that politics in Germany, and in Eastern Europe and Russia, became more militant,” says Empire. “We were speaking out against these things, and of course some people didn’t like that, and would try to shut us down, so we had to shout louder and fight harder. It wasn’t like you could sit down with these people and discuss their philosophies because they were always looking for physical violence. And it was important to us to take a stand. Musicians shouldn’t be like, ‘I’m into rock n’ roll, it’s not my problem’, because it will become your problem soon enough.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I don’t know if it was in the news much in England, but in the 1990s in Germany we had the NSU, a neo-Nazi terrorist organisation, and they were able to kill people without reprisals, with the Secret Services trying to cover it up because they’d sold them weapons. It was a big scandal that finally broke in Germany over the last few years, confirming a lot of the stuff that we were saying in the ‘90s. It was always very strange that you’d have these people armed to the teeth and beating people up and the cops just wouldn’t show up. It’s sad that in 2015 we’re still dealing with these idiots, and a new generation of idiots alongside them.”

ATR’s incendiary sound and in-your-face politics garnered the band fans on the metal, alternative rock, techno and hip-hop scenes, with Rage Against The Machine, Wu-Tang Clan and Ministry among the bands taking the Berliners on tour. The Beastie Boys signed the band to their ultra-hip Grand Royal label, editing and re-packaging their first two albums (Delete Yourself! and The Future Of War) for release as the Burn, Berlin, Burn! compilation in 1997. With artists such as The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers being hyped as the future of music, ATR were increasingly heralded as the cutting edge of a new noise revolution, and the likes of Slayer and Fear Factory signed up for collaborations.

“We didn’t swallow the hype, but it was a good time for our band,” Empire reflects. “When we were adopted by bands like Rage and the Beastie Boys that seemed kinda logical to us, because we were all coming from the same place originally, in terms of punk rock and hip-hop. Although we also toured with people like Nine Inch Nails and Ministry there was nothing ‘goth’ about our band: our music was always saying ‘Get Up and do something about the situation!’ rather than wallowing in self-pity and accepting your situation. We could never afford to think like that.”

Somewhat ironically, as with fellow Grand Royal label-mates At The Drive-In, ATR’s burgeoning popularity would ultimately lead to their demise, as the pressures of constant touring and non-stop promotion inevitably took its toll. The band’s 1999 Brixton Academy date (subsequently released as a 27 minute, single track album) wasn’t their final act, but following the recording of a one-off single, Rage, with RATM’s Tom Morello, the band dissolved, worn out by their high intensity lifestyle. The passing of Carl Crack in September 2001 following a drug overdose seemed to sound ATR’s final death knell, as Empire, Elias and Endo all embarked upon solo careers. In 2010 however, a new-look ATR resurfaced, with Empire and Endo joined by Detroit-born producer/DJ CX KiDTRONIK, releasing a fourth studio album, Is This Hyperreal? which, with its fierce mediations upon human trafficking (Blood In My Eyes), hacker activism (Codebreaker), surveillance culture (Shadow Identity) and the importance of civil disobedience (Black Flags, The Only Slight Glimmer Of Hope), showed that the band had lost none of their insurrectionary power.

The recently released Reset finds Atari Teenage Riot ready to step up to the barricades once more. Informed by recent revelations about government surveillance, human right abuses, corporate fraud and the creeping erosion of civil liberties, it’s a brilliantly forceful protest album for the modern age, but one which takes a surprisingly optimistic view of the future, acting as a soundtrack for what Empire hopes is a new age for humanity.

“If you listen to the new album, as compared to say, The Future Of War, which is very nihilistic, it sounds like a fresh start, with an energy comparable to our early releases,” he says. “We don’t feel like the world is ending, we feel like there’s a lot of people out there saying ‘Fuck this, let’s make something new happen!’ There’s a real different energy from, say, 1999, when people thought a computer virus would destroy the world! I’m sure there are people in Texas, or somewhere, that think the apocalypse is imminent, but I don’t get that sense elsewhere.”

In December last year Empire gave the keynote address at the world’s largest hacker convention, 31c3, in Hamburg, discussing his music, activism and his belief that culture and creativity can be used as a weapon in an hour-long speech entitled A New Dawn. It makes for fascinating reading (the full text can be found online here) and, taken in tandem with Reset, it illustrates that far from looking at the state of the planet with resigned weariness, Empire and his band are fully engaged and enthused for battles to come.

“There has to be tension and danger to create new music and push boundaries,” he says today. “So this climate makes sense for our band. We’ve always operated in a climate of confusion and fear: when we first played gigs people would be like (in a panicked voice) ‘Where are your guitars? Where are your instruments?’ because they just couldn’t handle the concept of this band. In recent years, the electronics scene caught up a little with that sound – with bands like Crystal Castles and Pendulum – so we had this new audience who didn’t consider that level of energy shocking, and now we can start to build again.”

“Reset is influenced by hacker ethics,” he continues. “In a way, Atari Teenage Riot came from that scene, because in the early ‘90s, when we were working with old Atari computers, the only people who knew about the technology were involved in that scene, so we’d get in touch when we needed repairs or certain old software tools. And that community was always populated by people who were involved in activism and had a general disrespect for authority. In the wake of the Edward Snowden revelations, I think more and more people have been educated to the importance of that community in exposing what’s really going on in the world, and this new album is very much a state-of-the-world address for 2015.”

As Hammer’s time with Empire draws to a close, we ask the 42-year-old Berliner whether being a member of Atari Teenage Riot in 2015 is actually fun. ATR’s frontman laughs heartily when the question is posed.

“We always had fun,” he insists. “There was always a large percentage of humour in our music… whether people could hear it or not. If you listen to our first album, which starts with the track Start The Riot, there’s a really quiet vocal at the beginning which most people never heard, saying ‘I would die for peanut butter’ or some silly crap, because we didn’t see ourselves as leaders of some movement and so we liked to throw in little subversive, silly things to kinda say ‘Don’t listen to us unquestioningly.’ But I guess being in ATR is like being in a band like Slayer – when you always exist ‘in the red’, it’s always fun to push things a little further….”

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.