“Anybody down there on acid seeing this figure flying down with flames coming out of his head must have thought God was coming”: The crazy life of Arthur Brown, the wildman who set rock’n’roll on fire

Arthur Brown is the flame-headed singer behind Fire – but that’s only one part of his insane life

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

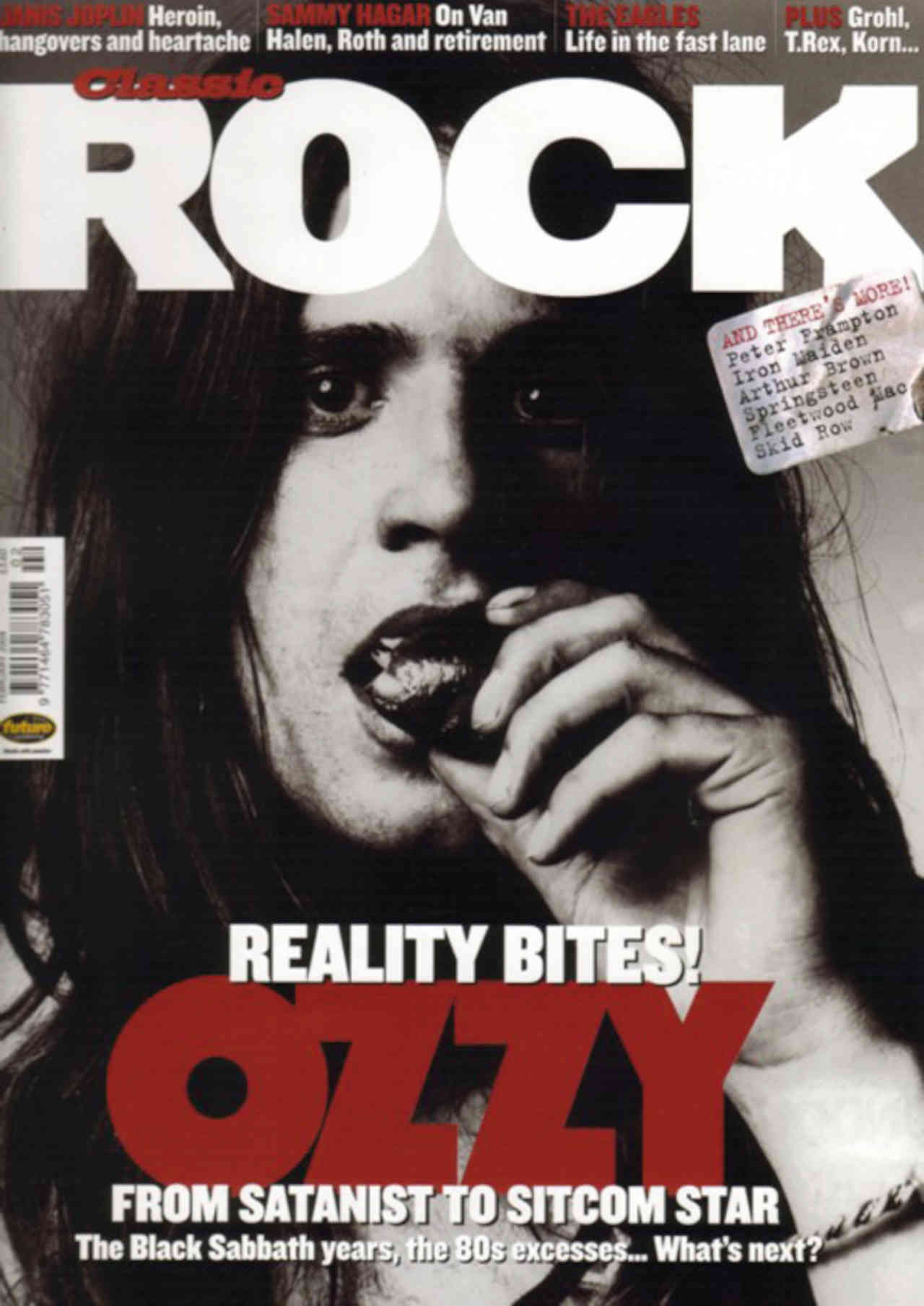

Arthur Brown is one of the great originators of rock’n’roll. As leader of The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown, his 1968 hit Fire inspired generations of shock rockers. But that was only the tip of the iceberg, as Classic Rock found out when we sat down with this great British eccentric in 2004.

Arthur Brown has always had a warm and intense relationship with Fire. That single (now a bone fide classic) reached No. 1 in the UK in August 1968 and No. 2 in the US chart a couple of months later. And although it was Arthur’s only chart appearance, it briefly took him from the shadows of being an underground cult figure into the full glare of rock stardom.

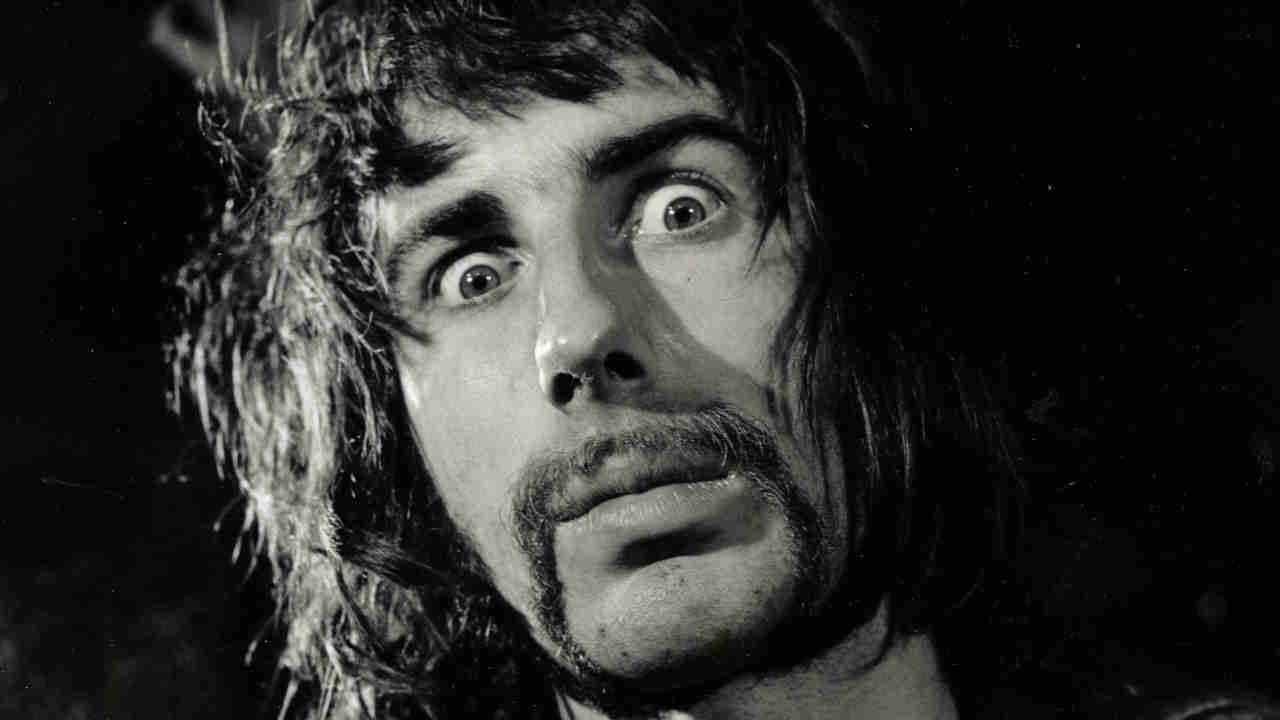

From time to time you’ll catch a grainy monochrome clip of manic-looking Arthur on some retro TV show, prancing about in his flaming helmet, sinister black-and-white face paint and outlandish cape, his voice building from the deep, resonant ‘I am the God of Hellfire!’ introduction to the song’s screaming climax. Even now, all these years on on such a vision makes compelling viewing.

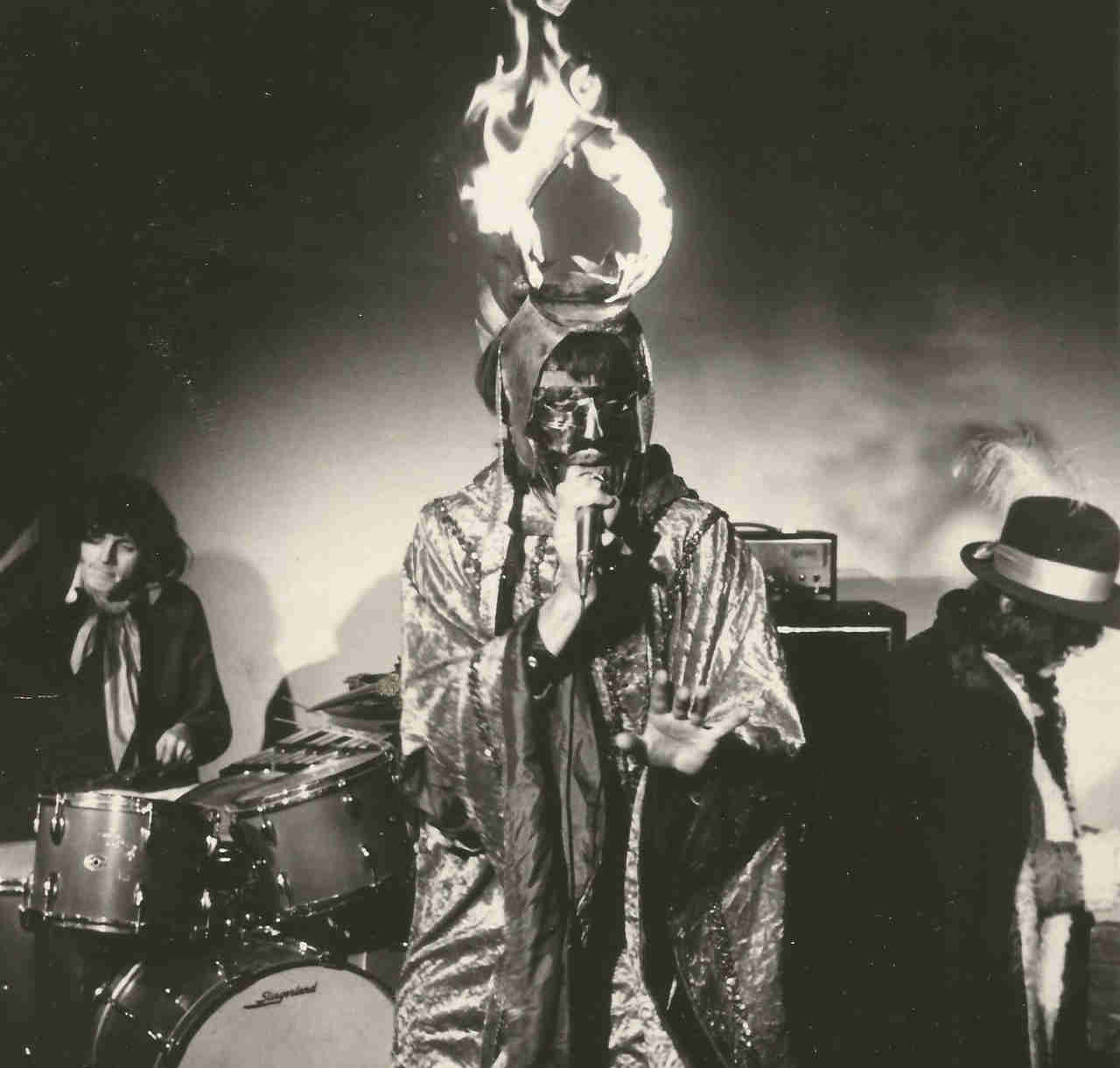

Fire was a cornerstone of The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown’s wild theatrical shows. And Arthur was always looking to give the act a spectacular twist. Like the time he made his entrance at London’s Roundhouse, swinging down a rope from the ceiling in full regalia, helmet ablaze. “Anybody down there on acid – and there must have been a few – seeing this figure flying down with flames coming out of his head must have thought God was coming,” he laughs.

Or the time at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival when he was lowered on stage by crane while similarly attired and ablaze. Except that a stagehand mistook his opening shrieks for cries of pain and rushed over and poured his pint of beer over Arthur’s head.

But Fire also gave Arthur Brown a brain haemorrhage nearly 30 years later. “It was a hot, sweltering club in Southend and I was singing the high note in Fire,” he recalls. “It was near the end of a thirty-eight-date tour and I was fifty years old. I’d also been trying out loads of different fasts, which had undermined my constitution.”

He survived, thanks to the National Health Service, and went back to recuperate in Texas where he’d been living since the early 80s. “But I was still in a bad way. I was having to learn to walk again. But the heat in Texas was starting to get to me. I basically stayed alive by folding napkins. It was all I could do. And then I wrote some really good songs. That part of me didn’t seem to disappear,” he finishes with a smile.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Texas seems a strange place for Arthur to have ended up. Stranger still when you discover he spent some time running a house-painting business with original Mothers Of Invention drummer Jimmie Carl Black. “I had married this lady from Texas and we had a child and I’d brought him up,” Arthur says by way of explanation. Which doesn’t explain a lot.

But then Arthur’s career was never going to be conventional, from the moment he ignored the questions on his first-year law exam at London University and substituted questions about Marilyn Monroe’s wardrobe instead.

That could have had something to do with being introduced to the Chelsea Set at the start of the 60s: a hip, swinging crowd who were into jazz, French films and dandy clothes. Suddenly Arthur’s musical tastes took on gourmet proportions: “I was guided by voices, really – Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Nina Simone, Joan Baez, James Brown…”

He was not invited to return to London University. When he switched to Reading University he kept his musical options wide open, singing in a jazz band, a folk duo and a mod/R&B band. The theatrical element came when he was offered a residency at a Paris club in 1964.

“Up until then I’d just been standing there singing. I didn’t know anything about stage acts. But playing three sets a night, seven nights a week, just singing the songs was not enough. I started to incorporate poetry, mime and sketches into the act. I’d come on holding a mop, with a bucket on my head, and pretend to be the Statue Of Liberty.”

Returning to England in 1966, Arthur wanted to expand his new-found art-rock talents and looked around for like-minded musicians – while narrowly avoiding becoming a member of the Foundations: “I was going to sing alongside Clem Curtis, and when I walked into the first rehearsal, above a bar in Westbourne Grove, the drummer was bent backwards over the bar and Clem was leaning over him with a spear at his throat.”

In fact the musician Arthur wanted was in the West Kensington house he was living in. “[Future Crazy World keyboard player] Vincent Crane was going out with the landlady’s daughter, and he had a couple of friends who used to come over and write songs. Vincent was a brilliant, classically trained musician with an immaculate taste in music, but he had not really started writing,” Arthur says.

“Together we developed this concept show. We started with costumes, and that led on to makeup, and then we got a proper lightshow. At that time there was virtually nobody else here that was linking lights to music and really going for it.”

But they still needed a drummer. An ad in Melody Maker got a response from drummer Drachen Theaker, who’d got caught in a traffic jam on the way to audition for the Jimi Hendrix Experience and called in on Arthur and Vincent instead.

Now there was some solid rock credibility for Arthur’s art-rock, and they started getting club gigs around London, including the Speakeasy, a fashionable haunt for off-duty stars such as the Rolling Stones. “They [the Stones] were apparently quite bemused by our set,” Arthur recalls. “It was before ‘Their Satanic Majesties…’ and all that stuff.”

Someone else who saw them at the Speakeasy was Joe Boyd, who had just started the underground UFO Club. The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown were just the kind of band he was looking for. Legendary as the club that launched Pink Floyd, UFO was not just about the music. Theatre troupes, mime artists, trippy lightshows and huge inflatable mattresses (this was way before bouncy castles) were all part of the night’s entertainment.

“It wasn’t so much a scene as a forum where you could explode,” remembers Arthur, who did just that. “That’s when the flaming helmet and the act really came together.”

Arthur would emerge through a haze of smoke, the flames from his helmet licking perilously close to the low ceiling tiles as he stalked menacingly around the stage, performing The Fire Suite accompanied by swirling rhythms and gothic, jazzy organ riffs. The lighting mirrored the action, switching to strobes when the going got frenetic. Quite how he avoided serious facial injuries while cavorting around with what effectively amounted to a saucer of burning lighter fuel balanced on his head remains an unexplained miracle.

“My hair was singed many times, my clothes caught fire once, and we were always leaving burn marks on stages. But my face only got burnt on a couple of occasions,” he says.

It was Pete Townshend who got Arthur signed to The Who’s managers Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert and their Track Records. Suddenly there was some commercial muscle behind The Crazy World. Their first single, Devil’s Grip caught the essence of the band’s creepy, compulsive style but didn’t have a catchy enough hook to chart. However, Atlantic Records in the US were keen for an album, and the band began recording The Fire Suite based around the song that was already a highlight of their set.

But Kit Lambert wasn’t happy with a concept album. “He wanted more cover versions like I Put A Spell On You,” Arthur says. “In the end he let us have the first side of the album while he had the second.”

It made for an uneven album, not helped by being recorded in different studios, although the highlights were pretty high. But that was just the start of the album’s woes.

“Kit took the album to America and Atlantic said: ‘It’s great, but the drummer’s out of time’. He came back and got Vincent to write some brass arrangements. The drums were buried; if you listen, it’s the brass that’s carrying it.”

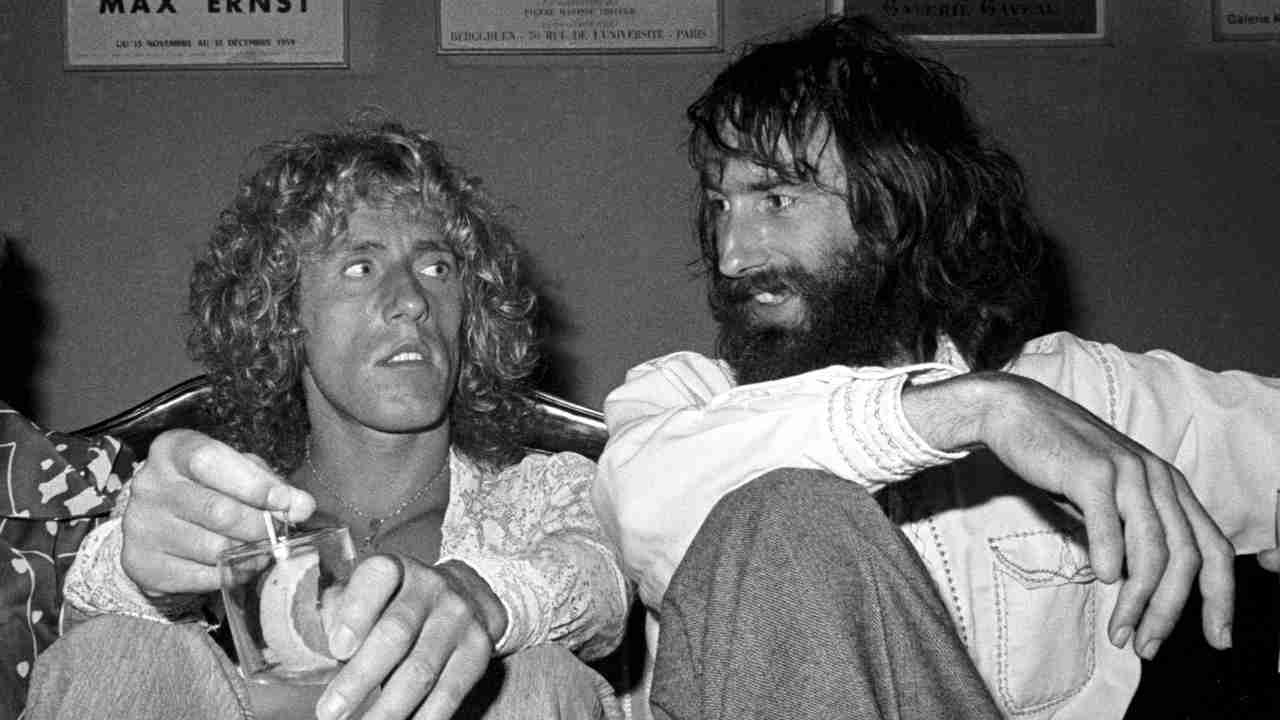

They were on their first American tour – supporting the likes of The Doors, Frank Zappa and The MC5 – when Chris Stamp arrived with acetates of the album. “We found a record player and put it on,” Arthur recalls, “and at the end of the first song Drachen walked across and said: ‘You fucking cunts!’ He picked up the record and hurled it against the wall.”

After that The Crazy World got crazier. “Drachen was already freaked out by the whole American experience, now he was angry. And Vincent was not happy with the way it was going. I was just managing to hold it all together.”

“Then one day Drachen, midway through the gig – whether he’d been watching Keith Moon too much I don’t know – kicks all his drums off the front of the stage. At least Keith Moon did it at the end! Drachen thinks it’s a great stunt until I start shouting at him, and then he walks off. Except that he falls off the front of the stage on to his own kit!

“Back at the hotel he’s really lost it. He’s running around the hotel with his trousers around his ankles, thrusting his wobbler up against the windows. Then Vincent comes in and says: ‘Right, either I go or that fucking wanker does’. I’m trying to calm him down but he’s adamant. I know I will not be able to replace Vincent. So I go to Drachen and say: ‘I’m afraid you’ll have to leave’. And he says: ‘Right, I’m going now’. So now we have no drummer.

“Someone recommends this Canadian guy. He’s a really good groove drummer. The next thing, Vincent starts to get the James Brown vibe. He buys all his albums and plays them constantly. In fact he starts to go over the top. He begins to speak in numbers – ‘You’re the one. Two. Arthur three. Four. Maybe five’. And there was an aggressive undercurrent about it. We thought someone had spiked him. But it turned out he was manic depressive.

“Just as we’re starting one show, he sees a crate of beer that some fool has left at the front of the stage. He walks across while I’m lighting my helmet and starts throwing the cans at the audience. So I go over to him and push my flaming helmet into his face; I push him back round to the keyboards and he sits down. I nod at him and he starts to play. And the show was fantastic. But the next day he was back to speaking in numbers. And after eighteen hours we’re exhausted, because if you weren’t paying him attention he’d break something.

“We got to the hotel, cancelled the gig, then locked him in a cupboard while we went to look for some food. When we got back the cupboard’s smashed open – no sign of Vincent. We eventually found him on the main street, wearing just a cape that he opened from time to time, trying to hitch a lift. And there’s a police car heading toward us. So we grab him and run back to the hotel with him. And just as we get into the room there’s a phone call: ‘When are you arriving for the soundcheck?’ ‘But we cancelled the gig’. ‘No, your keyboard player rang earlier and said it’s on again. And now people are turning up’.”

Vincent was invalided back home. Arthur limped back soon afterward, having somehow managed to complete the tour with stand-in musicians. But if he was looking for sympathy from the management, he was wrong.

“Chris and Kit had always seen me as a solo star. They didn’t think the underground thing was going to last. Kit called me in and said: ‘You can do your underground nights at the weekend. But the rest of the week we want you to play in the lounge. We’re going to make you as big as Engelbert Humperdinck’. And the funny thing was that Engelbert’s people actually came on to me as well. They also wanted me to change my image – shave, haircut, maybe even a nose job. Kit even suggested I could wear a wig for the underground gigs. I just looked at him incredulously and said: ‘No, you’re joking. You just don’t understand me at all. The Crazy World is where I’m at.”

To be fair, Stamp and Lambert had a point. The range and operatic qualities of Arthur’s voice are exceptional, and he could have been moulded into a successful solo artist. But the concept of Arthur Brown as some Bryan Ferry-style crooner is more surreal than any of the characters he has invented over the years.

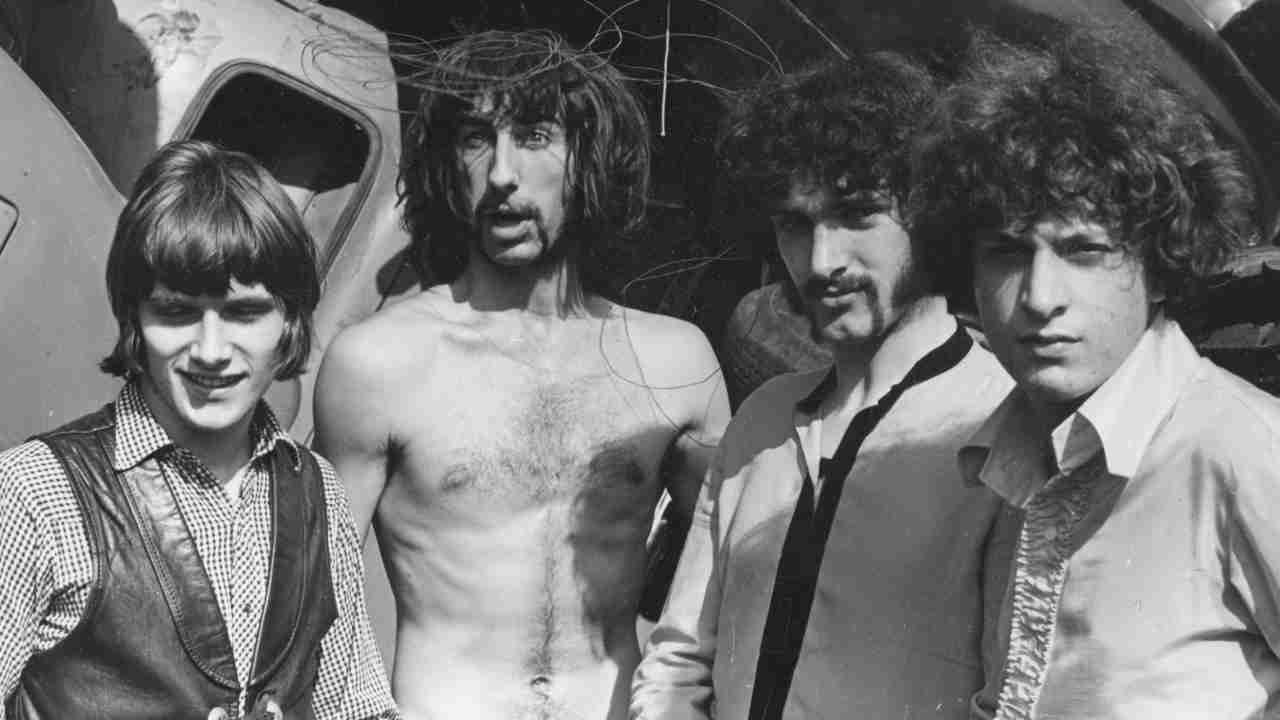

So it was back to The Crazy World. Or at least it was once Vincent Crane had recovered. And they struck lucky with their next drummer, Carl Palmer, who was fresh out of Chris Farlowe’s band and a potent musical match for Vincent.

“Carl’s arrival changed the whole style of our music because he was much more of a technical drummer,” Arthur says. “Vincent loved that, and they also got on well together which was great because it was just when Fire was a hit.”

The Crazy World were hastily dispatched for another American tour. And this time it was Arthur’s turn to flip. “Before the first American tour I’d never even touched a joint. On the second tour I took acid and that changed everything. I had a completely different realisation of what was going on.”

This new realisation culminated in the infamous Houston Holiday Inn Experience that began when Arthur checked in, wearing white robes and carrying two suitcases. He was shown to his room and, still carrying the suitcases, walked through it on to the patio and straight into the pool. Minutes later he emerged from the pool, dripping, still carrying the cases, returned to reception and asked for another room on a higher floor.

At sunset, drivers on the highway were confronted by the sight of the full Arthur Brown stage show from the balcony of his hotel room – including smoke, strobe lights and psychedelic effects. Complete but for one small detail: Arthur’s clothes. He wasn’t wearing any. He had, however, remembered his helmet.

“There was pandemonium out on the highway,” he remembers. “There were pile-ups, it was completely blocked. There were probably a thousand people watching, and the police were trying to get through on their bikes. Then we got put in jail. Which in the US is not very pleasant.”

Things really started to disintegrate when Arthur contrived to turn down a £650,000 advance for their second album.

“We had a new stage act about a black magician,” Arthur explains. “Our American managers set up a deal with CBS and we’d recorded a song that they thought was bound to be a hit. But we were under contract to Track Records. So we had a meeting in a hotel with Chris and Kit upstairs and the American management downstairs; I was going up and down in the lift between them. But I eventually decided that whatever Chris and Kit’s shortcomings – and I did leave their management later – they had got us up there and it was not morally fair to walk out at that point. I think Vince and Carl thought I’d lost my marbles. We played more gigs, but it wasn’t really going anywhere after that.”

There was also the saga of what could have been: the possibility of forming a band with Jimi Hendrix. “We used to play a New York club called The Scene, and Hendrix used to come down. We got to know each other a little bit and he’d come up and jam with us. He’d play bass, he’d never sing even when I asked him. He hated singing, but he was a fucking great bass player!

“One night I was summoned to his hotel and he told me wanted to put something together with me and Vincent. He had this whole idea of screens, and tapes of Wagner playing in the background. He was in something of a reverie, but he could focus on anything musical.

“At the time, however, I was in a state of nervous exhaustion and could do little more than nod agreement. I know he made a similar suggestion to Keith Emerson later, but I was flattered even to have been asked.”

The flattery is enough to withstand a deflating comparison with Hendrix as a lover, from someone fully qualified to judge. “She told me: ‘Your love-making was okay, but Jimi takes me right to the edge, until it feels like I’m going to fall into an abyss. It goes on like that for a long time. You don’t do that’.” Arthur’s voluntary humiliation in the cause of the Hendrix legend is truly commendable.

But none of it was enough to prevent The Crazy World from imploding soon afterwards, Vincent and Carl heading off to form Atomic Rooster. Arthur, meanwhile, decided to follow his spiritual instincts – something that was to be a regular occurrence over the next decade.

“I’d gone through this whole spiritual growth thing in America, and it transformed everything; not only what I wanted to do with my music, but also how I wanted everything structured. I decided there was no place for leaders, and democracy didn’t work either; there was no room for hierarchies.”

It’s fair to say that an anarchic spirit pervaded Arthur’s next group, Puddletown Express. Their act included the Fire Rite that involved Arthur in a ritual dance with his Crown Of Flames before making a grand disappearance, only to reappear… naked.

The band’s groundbreaking artistic endeavours were not always appreciated; the French Communist Party reckoned that a so-called benefit gig by Puddletown Express cost them a parliamentary seat. And following a spot at the Palermo Pop Festival, Arthur found himself thrown into Sicily’s maximum-security jail.

Not surprisingly, Puddletown Express was short-lived. And while its successor, Kingdom Come (not to be confused with the 80s Led

Zeppelin clone), had a similarly loose structure the music was more focused and innovative. Kingdom Come’s first album, Galactic Zoo Dossier, was released in 1970 and could have been a successful concept album if it had been given the full-on production and direction by a ‘name’ producer. It certainly left a mark on Alice Cooper, who had already been studying Arthur’s make-up carefully.

While Kingdom Come‘s self-titled second album was a rather muddled venture into the theatre of the absurd, 1973’s Journey broke new ground with its use of a primitive drum machine. The fact that Arthur was forced into using it because his drummer had run off with the bassist’s wife should not detract from his pioneering use of technology.

But without proper management and promotion, Kingdom Come were always going to struggle. After touring the Journey album for a year, Arthur removed his body and soul to a school of Sufism (Islamic mysticism) in Gloucestershire; his band went off to join singer Kiki Dee.

Arthur’s career for the rest of the 70s was seldom dull. He pre-empted the world music brigade by nearly a decade with his 1975 album Dance, using African, Eastern, reggae and disco beats on various tracks. He also guested on Alan Parsons’s Tales Of Mystery And Imagination and Klaus Schulze’s Dune’ and Live albums.

Then there was his appearance in the movie Tommy that should have been more than it was: “Pete Townshend originally wanted me to be the doctor or the Pinball Wizard, but the man in charge of it all was Robert Stigwood, who I’d fallen out with back in the Crazy World days. So I ended up sharing Eyesight To The Blind with Eric Clapton. But on the later soundtrack it’s just Clapton.”

Arthur’s free-spirited artistry was incompatible with punk, which is another reason why he spent the 80s and much of the 90s in Texas. He wasn’t entirely inactive musically, however, and released a couple of industrial/electro albums in the US.

The embers of Fire were periodically stoked by cover versions from Marc Almond, Pete Townshend, The Ventures, Prodigy and Die Krupps – Arthur even helped out on the latter. He returned to England in the late 90s after linking up with Big Country’s former manager Ian Grant, who was, just by chance, setting up a record label called Track Records. Grant had even secured the label’s original logo, though not the original label’s now priceless catalogue.

After re-establishing himself on tours with Robert Plant and The Pretty Things and festival shows at Glastonbury and Canterbury Fayre, in 2003 Arthur recorded a new album, Vampire Suite, with Big Country drummer Mark Brzezicki and keyboard player Josh Phillips.

“The idea was to get back to the original format of The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown. It’s about a vampire who gets redeemed after attacking someone who turns out to be a saint. It’s a dramatic story, full of hyperventilating falsettos and screaming. And darkness, too.”

Arthur Brown. Still crazy after all these years.

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 63

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.