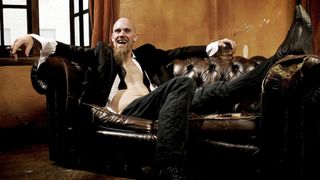

From Kyuss and Dwarves to Queens Of The Stone Age and Mondo Generator, Nick Oliveri has always been the wildest member of every band he’s been in. Fuelled by a cocktail of drugs and mind-crushing boredom, the often-naked bassist was a desert-rocker from day one thanks to his upbringing in Palm Springs, California. He’s been kicked out of QOTSA, drunk his way across the globe and bounced back from multiple arrests including one domestic incident that saw a SWAT team descend on his home in 2011.

So it’s no surprise that, as he looks back on his formative years, he neither sugar-coats nor romanticises his party-hard, worry-later background that paved the way for him to become the desert’s most unpredictable bassist.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Los Angeles on October 21, 1971. I lived in LA, I guess until I was 11, and then grew up in the desert. I’m still growing up anyway! But yes, my adolescence was in the Palm Springs area.

What was growing up there like?

Pretty weird. I didn’t really belong there I don’t think. Too many rich families, a lot of old money. It was very strange. It was a growing area and my mom got a job out there so we ended up in the desert. It was very strange. But I wouldn’t be playing music if I hadn’t moved there, so it was a positive thing.

What was your childhood like?

Good. Lots of trouble but just normal kids stuff.

What were you like at school?

I had a contest with a guy to see who could get the most referrals. That kind of shit. I won. I was kind of a jackass. It was fun. I had a good time, listening to music and stuff.

So what got you into music?

I have to say Black Sabbath. Paranoid was the first one I heard. I heard it through my uncle. I had a little guitar from Tijuana. A little Spanish guitar I didn’t know how to tune so it left me bloodied and blistered and I didn’t know how to play it. But I kept going and my uncle, this big biker, gave me Paranoid and said, “You’re going to make music one day”. I was really into Kiss. And I was really into Evel Knievel – he didn’t play music but he was like a rock star in the USA.

Did you have one of those Evel Knievel wind-up toy bikes?

Yes and it was real too because it crashed every time, ha ha ha! It was real true-to-life toy.

How old were you when you decided to play music?

I knew that was what I wanted to do when I was 11. I stopped caring about school so much and stayed at home trying to play my guitar along to Kiss and Ramones records. I could figure the Ramones out. The guitar came out of the right side of my stereo and the bass out of the left. That was my teacher.

How did your parents view your burgeoning enthusiasm for music?

My parents were happy they didn’t have to pay for any college. My brother was quite good at school and I think they were trying to figure out how they were gonna pay for me too. But he didn’t end up going either so it all worked out and I chose music.

- Kyuss: It Came From Out Of The Desert...

- Confessions: Nick Oliveri

- The 11 best Queens Of The Stone Age songs chosen by Jesse Hughes

- The A-Z of Josh Homme

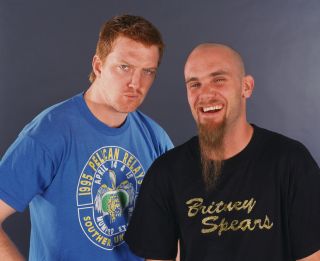

What was your first band?

It was a band called Katzenjammer, which was really the beginning of Kyuss back in 1987. When you’re a kid you make up a band, even though you don’t have one. The Done Controllable, I called it. I still think it’s a great name. I had a logo and stuff even though I didn’t have a band. But 1987 was the first time I played with a drummer, with other people. It was Brant Bjork on drums, Josh [Homme] on guitar and me on second guitar. I sang at first because John Garcia, the singer, was late getting there. Chris Cockrell played bass. That was the first version of Kyuss. We played a party, we only had enough songs to play a party. Back then in the desert there were no gigs or venues so you played parties. That was the gig.

Kyuss are very much tagged as defining the stoner/desert rock sound. Was that something that was evident from the start?

No. It’s funny because people didn’t really care about Kyuss. Maybe over here, but over there definitely not as much as they do now. There’s so much interest now, and has been for the past few years. It’s quite ironic. We always looked at it as we didn’t want to do too well, and we never did. We were always nervous that our friends back home were gonna think we’d sold out or we were weird if we did this or that. We made a lot of self-sacrificing choices because we were worried about what people were gonna think in our hometown.

Did that specific way of thinking derive from the lack of gigging opportunities you had in the desert?

We were the first band from the desert to go to LA and start playing. It was full of the hair metal bands and we were just these long-haired hippie freaks. So it was a different vibe. We looked down on it and people looked down on us. We’d go there and end up in fights. Some of our early ads even had, “Come and see Kyuss fight! Oh yeah, they’re gonna play too” on them! We knew that if we were ever gonna do anything other than play in the desert we were gonna have to spread our wings and be bigger than a small town.

Sabbath were obviously a big influence on Kyuss as well.

The first six records especially. Diamonds – every one of them.

How did it feel to be thought of as originators of the desert/stoner thing?

Kinda cool, in a way. I think Josh kinda frowns out about that a little bit. And maybe John does too, but I think it’s cool to be recognised for anything that’s a kind of movement. I always thought “Why shouldn’t we embrace that instead of looking down our noses at it? Wow man, someone likes what we did.” I think maybe Kyuss was Josh’s thing, and later on John and Josh, those were the guys when I was in the band who’d come up with the ideas. I had some co-writes, but we’d often choose their songs over our own. It was really their vision and their thing and I’m proud to have been a part of it. But I think it’s a shame they don’t go “Stoner rock? Cool man!” I think it’s a tip of the hat if someone says you started or influenced something.

Was the original Kyuss sound the one most people know and love the band for?

I think we were a bit more punk in the beginning. We didn’t have a tuner but we were tuned down to B and that’s where the Kyuss sound came from. Later on with the second record we tuned up to C. It actually created a cool sound and we stuck with it. I prefer the Sky Valley record – I’m not on it but I think it’s the best Kyuss record where I really think they started out finding where they were going and what they wanted to do. It’s a cool record man.

The perception is that you left Kyuss to join The Dwarves because you wanted to be more punk rock. True?

Yes and no. If you look at Blues For The Red Sun there’s a picture of my old man there and he’d just passed away. I was partying a bit too much and I was kinda asked to leave. But I was also going in a more reckless vein. I was really into the jamming aspect of it but I was going in a more aggressive musical direction too.

Drink and drugs seem to have gone hand-in-hand with you throughout your career. Where did that start?

In the desert there’s nothing to do. If you’re into music and the music I’m into, part of it was centred around having a good time. Girls and drinking and partying and whatever. That’s kind of how it started. There’s a lot of cool bands out in the desert that only people out there know. They were very influential on us and on our vibe. We had a good time. There’s down moments in everyone’s life but I’ve always enjoyed having a good time with my friends. Or myself. I guess when it’s not fun anymore I’ll reconsider. I’m still having a good time.

Where did the predilection for performing with no clothes on come from?

Being pushed in a pool with clothes on. And then getting out and playing a show and feeling yeuch. I think people

in America are really weird about nudity.

Same in England!

They can be too, but in Europe you see things like a billboard with a nude girl selling an ice-cream bar and you’ll be like, ‘Shit, I’m gonna buy that bar!’ I don’t think it’s really frowned upon in Europe, not a big deal. I just feel it’s not anything great to look at, it’s just a nude guy. I think it’s more scary than anything and I like to scare people. I also like to feel free and it’s a good, free feeling.

Was going from Kyuss to The Dwarves a bit of a culture shock for you?

It was good actually because I knew all the stuff. The first time I went to see them, with Brant Bjork, Blag [Dahlia, Dwarves frontman] punched me in the face. I turned back to hit him and then the drums went over and the show was over! But they were the first band to take Kyuss on tour. It wasn’t that much of a jump for me because I always liked fast, hard music and I was listening to them so much. The stuff I was coming in with for Kyuss was like four minutes and faster, instead of eight minutes, so I was going in a different direction. It worked out.

What prompted a return to work with Josh in Queens Of The Stone Age?

I was living in Austin, Texas and I had Mondo Generator going in 1997 and he came down with the first rendition of Queens. It wasn’t that great. I think Josh has only just now gotten comfortable singing. Josh and Alfredo came down to see us do a gig in this little Blue Flamingo punk bar. I had all my clothes off and I was drunk and Josh asked me if I wanted to play with him again. Being the arrogant son-of-a-bitch that I am I was like, “Send me a cassette, I’ll let you know”. He did, I dug it, called him up and asked when he wanted me to come out. I went back, we hit it off again. Somehow with our chemistry it made sense for us to play music together.

You were immensely successful.

Yes, I’m very proud of the stuff I did with Queens. Fortunately I haven’t done anything musically I don’t like. But the Queens stuff was great, I can hold my head up and feel good about it. We worked together very well and I’m sure we’ll do some stuff in the future. I always leave stuff like that open down the road. But it was crazy successful, and all new for us and we hadn’t experienced it before. A bit scary as well.

What happened between you and Josh?

I think we’d just done so much together and worked so closely together over the years that eventually we just didn’t hang out as much as buddies anymore. We talked to each other but not in the way we used to. But that happens. And we had a break coming up, and during the break he decided he didn’t want to do it with me anymore. Shit happens, you can’t force people.

Disappointed?

Yes. For sure. I really felt it was my band too, not just his. To turn your back on that is crazy to me.

But you’ve stayed busy with Mondo Generator in the meantime.

I try to. I try to stay busy with all my friends whose bands I like. If they want me to be part of it I’m always honoured and I try to give 100 per cent every time. I give it everything.