Rob Halford can remember exactly where he was when he heard Turbo Lover in public for the first time. It was early 1986, and the Judas Priest singer was driving down Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip when the opening track from the band’s 11th album, Turbo, began blasting out of the radio.

“It’s a very vivid memory for me,” he says, his Walsall accent undiluted after all these years. “I’m driving a convertible Mustang with the top down, and Turbo Lover starts playing. I’m driving along, banging me head, all these people watching on the sidewalk. I know it sounds like I’m posing when I say that, but it was the best feeling in the world.”

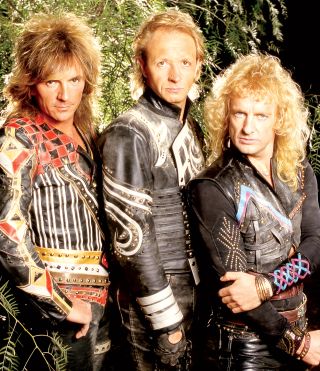

Having spent the previous 15 years slogging their way from the booze’n’nicotine-stained pubs and clubs of the West Midlands to the arenas and stadiums of the world, the members of Judas Priest were rightly fired up by Turbo. This was the sound of a band moving with the times and engaging with leaps in technology – synths and shiny production and frothy, good-time lyrics were in. This was the gleaming new Judas Priest. The problem was that a lot of their old-school fans wanted the not-so-gleaming old Judas Priest.

Even worse, Turbo marked the point where Rob had hit rock bottom in his personal life, weighed down by alcohol and drug addiction and marred by personal tragedy.

“It was a dark part of my life,” he says now. “I had to get myself sorted out, otherwise it would have been six-feet-under time.”

More than 30 years after it was originally released, Turbo remains the sore thumb in the Judas Priest catalogue. Received wisdom pitches it somewhere between a cynical sell-out with one eye on the pop market and outright career suicide.

Neither is true. As a brand-new reissue proves, Turbo may have been a departure on the surface, but at heart it was a classic Priest album – and an honest one at that. On a commercial level, it was far from a flop thanks to mainstream American radio and MTV picking up on the singles Turbo Lover, Locked In and the anti-censorship broadside Parental Guidance. “It lost us some friends,” says Priest bassist Ian Hill, a mainstay of the band since their very beginning in Birmingham at the end of the 1960s. “But it made us as least as many as we’d lost.”

Priest were coming off the back of a stellar run of success when they began work on Turbo. While their late-70s and early-80s albums had enshrined them as one of Britain’s pre-eminent metal bands, the platinum-plated one-two of 1982’s Screaming For Vengeance and ’84’s Defenders Of The Faith had turned them into bona fide rock stars in America.

“We were on top of the world,” says Rob, a man whose drily lugubrious manner is amusingly at odds with his Metal God persona. “After slogging away for years, we’d suddenly reached that place all bands strive to get to, which is success. It was an amazing time, not only for Priest but for metal in general.”

After touring Defenders Of The Faith, the band gave themselves a much-needed break. When they reconvened in Marbella in southern Spain in early 1985, they were keen to throw themselves back into the fray. But the last thing they wanted to do was merely repeat past glories.

“Some people would have been absolutely over the moon if we’d done another Defenders Of The Faith,” says Ian. “But we felt like we’d reached the end of the line with that. Some bands get a formula and they stick to it, and people love them for it. But we’ve always moved forwards.”

As they soaked up the sun in Marbella, they began to realise that things had changed since they had been away. Launched just a few years earlier, MTV had become a music industry powerhouse with the power to make or break bands. Many of Priest’s peers had latched onto this and altered their approach to fit this revolutionary new format, chief among them ZZ Top and Billy Idol, who had begun incorporating the latest technology into their sound and serving up eye-catching videos to fit in the heavy rotation slots. “We were definitely aware of what was going on with MTV,” says Rob. “It was a gamechanger. It totally changed the face of music, which probably had some influence on the general outcome of Turbo.”

- Judas Priest’s Rob Halford thanks NHS staff: “You are angels”

- The 50 Greatest Judas Priest songs EVER

- Watch Lars Ulrich attempt to sing Judas Priest’s Delivering The Goods

- Watch Metallica’s blistering homecoming show from San Francisco in 2017

Understandably, when electronic instrument company Roland approached Priest to see if they would be interested in being the people to try out a brand new guitarsynthesizer they had developed, the band jumped at the chance.

“It basically took the straightforward sound that you normally get if you plug a guitar into a Marshall amp, but let you alter the sound completely,” says Rob. “It could give you a non-guitar sound. That was at the heart of Turbo. And that, I think, was part of the pushback from the purists in metal: ‘Why are you messing with the sound? That’s not the Priest we want to hear.’”

The band weren’t oblivious to the ramifications of what they were planning when they flew to the Bahamas to begin work on the album at Nassau’s Compass Point Studios with longtime producer ‘Colonel’ Tom Allom, but they were still determined to push forward. It wasn’t the only radical decision they had made. The original plan was that the new album would be a double, titled Twin Turbos.

“We wanted a double album for the price of a single one,” says Ian. “The label weren’t happy about that. They couldn’t manufacture the album and flog it for what we wanted them to sell it for. So about halfway through the writing process, we decided to go with it as a single album.”

Some of the tracks written for Twin Turbos would appear on their next album, 1988’s Ram It Down, while others would feature as bonus tracks on subsequent reissues.

But clashes with their record label were the least of Rob’s worries. The singer had his own battles to deal with. Ask him today what someone might have seen if they’d have walked in halfway through the sessions, and he laughs drily.

“I’d probably have been in the corner with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and a mound of coke,” he says. “I was out of my fucking tree. That’s where I was at personally. It was a point where I needed help. I don’t know how the guys coped with me.”

“We all went over the top in the 80s,” says Ian. “If you weren’t going over the top, there was something wrong. But we didn’t realise quite how far gone Rob was.”

Rob’s state of mind wasn’t helped by the exotic location. “There were tremendous distractions,” he says. “We’d start work at six o’clock at night, then Tom Allom would have his gin and tonic and that was the end of the session. We’d all go down the pub and get loaded. We had to get the hell out of the Bahamas. Somebody said, ‘Why don’t we go to Miami instead?’ Oh yeah, great idea. ’Cos there were no distractions there either. Ha ha ha, oh my god.”

Instead, the band moved their base of operations to Los Angeles. It was there that Rob checked into rehab. “I came out after 30 days and my life had changed in a million ways,” he says. “The important part was my ability to understand that music is the most important thing in my life and that I don’t need any other chemical influence to do what I need to do.”

He may have been clean and sober, but life had one more tragic twist to throw at him. In 1986, Rob’s boyfriend at the time killed himself in front of the singer. He’s reluctant to talk about specifics, but his voice takes on an understandably solemn note when he recalls the impact it had on his life.

“I was with someone who was also dealing with their own self-destructive challenges,” he says. “That was my pledge, in the memory of that person, to stay clean and sober. In fact, I just passed my 31st birthday last week. But drug addiction and alcoholism is like a curse, man. Bands ask me about the drink and the drugs, and I say, ‘Fucking do it, it’s a rite of passage – I hope you have a good time with it and I hope it doesn’t kill you.’ Because it can, and it does.”

Ironically, given Rob’s own personal turmoil, Turbo is resolutely uplifting, defiant and even sex-obsessed. It’s there in the titles: Turbo Lover; Hot For Love; Reckless; Wild Nights, Hot And Crazy Days. Even the album’s cover illustration of a woman’s hand clutching a gear stick is a barely disguised visual innuendo.

It also features Parental Guidance, a winking dig at the PMRC, the censorship group who had included Priest’s song Eat Me Alive on their so-called ‘Filthy Fifteen’ – a list of songs that they claimed threatened the moral fabric of America. The PMRC successfully campaigned to put ‘Parental Guidance’ stickers on albums containing explicit material.

“We couldn’t believe our ears when we heard about it,” says Rob. “It’s one of those things that only happens in America. I remember the day we said, ‘We should write a song called Parental Guidance. Take a walk in my shoes and see what you’re afraid of – it’s not real. As it turns out, Turbo was a commercial success, one of the biggest ones Priest had. So the PMRC thing didn’t have any knock-on effect.”

That commercial success must have seemed a long way off when the album was released in April 1986. Initial reactions in the press were at best baffled and at worst outright hostile. More importantly, its synthesized sounds alienated a chunk of their fanbase who wanted Priest’s traditional steel-plated twin guitar attack.

“It was a bit of a kick in the balls. It’s not nice to make a record and somebody goes, ‘This is shit.’ But this is the balancing act – you have to write from the heart, for yourself. You need the opportunity to express yourself and bang into things when you do.”

Age has been kind to Turbo. Its unconventional approach may have scared the horses at the time, but today it sounds shockingly modern. And its opening four tracks – Turbo Lover, Locked In, Private Property and Parental Guidance – are stone cold pop-metal classics, guitar-synths or not.

“It was a grand experiment,” says Ian. “We weren’t sure what the reaction would be, but we believed we were doing the right thing. And that’s why it’s honest.”

“The original kickback has mellowed over the years,” adds Rob. “People appreciate it now for the songs. They’ve embraced it. We could bang out any of those tracks live now and they’d do the business. Judas Priest are this band that has many metal heads attached to its shoulders, and Turbo has become part of the legend.”